Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 311th Regiment of the 78th Division

Getting Ready for Combat

“Everyone out for bazooka practice,” was the sergeant’s command.

“Everyone out for bazooka practice,” was the sergeant’s command.

We were stationed at Piringen near Tongeren, Belgium and were scheduled to go into the Hurtgen Forest soon to replace the 13th and 28th Infantry Regiments.

Many of us in the 2nd Battalion Headquarters Company had never actually fired a bazooka before. It was time we learned since the German 88 --- the tank with a mean gun --- was hard to stop. A bazooka round in the treads was one way to halt the beast.

Since we were limited in the space we had, the target range was near the Battalion Headquarters and the commander’s tent was directly behind the shooting range. Unfortunately, it was too close to the range. And when I was ordered to fire my first bazooka round at a moving tank target, the backwash from the tube started a fire in the wall of the commander’s tent. Nearly burned it down.

The commander came storming out of the tent demanding to know what “son-of-a bitch” was trying to barbecue him. The sergeant smoothed things over and I was never charged with attempted murder of a superior officer.

Oh, and I hit the target. Never fired a bazooka again, though. For some reason, they never allowed me near one.

The Hurtgen Forest

I was now a switchboard operator and wireman for the Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 311th Regiment of the 78th Division and our first combat assignment was the Hurtgen southeast of Aachen. It was Dec. 9, 1944. We stopped at our bivouac area located in a tall clump of trees. Telephone wires hung across the entrance to the area, blocking our 2 and 1/2 ton trucks.

“Finnegan, get out and raise those lines,” the company commander ordered.

I left the truck and found a pair of climbers, strapped them on and walked over to the trees at the bivouac entrance. As I did, I passed a line of weary, unshaven, dirty GIs who obviously had suffered during their weeks in the forest. They were straight out of the Bill Mauldin cartoons that appeared in Stars and Stripes. I reached the first tree, stomped my spurs into the bark and began the climb. When I reached about 8 feet I began hearing strange whizzing noises in the trees. Not bees in this weather. Winter was here. I ignored the sounds. I raised the wire another several feet, climbed down and went up the tree on the other side of the road. Same sounds as I reached the top. I ignored them. When I returned to the ground and walked back to the truck one of the GIs called me over.

“Hey, kid,” he said. (I was 20).

“You notice anything funny up there?”

“Only some whizzing noises,” I said. “Why?”

“Well, kid,” the GI said drawing on a cigarette butt, “we’ve lost a half dozen men lately from sniper fire who were doing what you just did. You were lucky.”

I didn’t ask him why he hadn’t warned me about the potential danger before I went up the trees but I guess it was just as well. I’m not sure how I would have reacted if he had.

Our stay in the Hurtgen Forest ending in two weeks . We moved south to Simmerath, which was just east of the Belgian border and the northern end of the German antitank fortifications, the Siegfried Line.

Our battalion was strung out in a series of pillboxes and foxholes just north of the Kall River. The Germans had planted the forest with all types of land mines: anti-tank and anti-personnel including bouncing Betty’s. Those were the mines that once set off by a GI’s foot, sent another charge into the air that exploded, showering shrapnel over a large area about waist high. A number of our troops lost feet and legs to those weapons.

Our battalion headquarters was located in a shattered German pillbox. While it provided cover from the occasional shelling that we were subjected to, it did not protect us from the elements entirely. Winter began just as we entered the Hurtgen. First cold rain, then heavy snow pushed by a bitter cold wind. We learned quickly that the pill box leaked. As we warmed the interior, that melted the snow and small rivers snaked inside the concrete walls. Within several days, there was six inches of ice-cold water covering much of the floor.

Most of us had overshoes since combat boots only hold out the water and cold for so long. It was tougher on the guys in the foxholes who had to stand in ice water nearly 24 hours a day. The order came down: massage your feet every couple of hours and try to dry your feet and change into dry socks. A lot easier said than done. Most of the men had only three or four pairs of socks, few places to dry the wet ones and few places to go to dry their feet. I was more fortunate. Since I was working the switchboard in the pillbox, I sat in a chair out of the water and could hang my wet socks on the board while I massaged my feet. I soon discovered that I could operate the switchboard with my feet. I found I could pull the cords from the board or put them in the proper connections by running the cords between my big toe and the next digit. I could also ring up the recipient of the incoming calls by turning the hand crank the same way. To this day there is still a gap between the big toe and the other digits on my right foot. We did lose a number of men to trench foot. For a number of days those casualties outnumbered the wounded in the battalion first aid tent near our pill box.

Laying Wire

The sky was clear; the moon bathed the crystalline snow with yellow light. At 10 below zero, the snow crunched like Rice Krispies under my combat boots.

We hadn’t heard from G Company for several hours; a radio call finally confirmed that the wire lines had been cut. New lines must be established quickly. It was obvious that the Germans were intending some kind of action – there had been a great deal of activity in their front line areas for the past several days. G Company had lost several outposts and phone contact to others had been repeatedly cut. No one thought that any major operation was imminent but it was clear that we needed to keep all our communications links open.

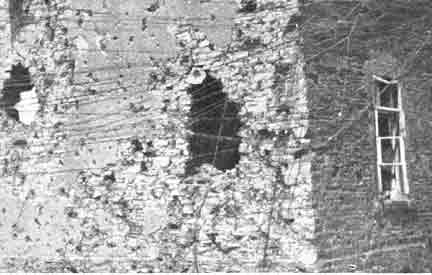

A maze of wires on a bombed out headquarters building gives an idea

of how phone lines were critical to communication at the battle front.

It was my turn to assist in the wire run. Although my primary job was to operate the switchboard at Second Battalion headquarters, I was part of the wire team rotation. That meant that every two or three days I would help crew the jeep assigned to run wire out to the infantry companies. Three men were needed. One driver and two to keep the wire running smoothly off the large metal reel located in the rear of the jeep. We weren’t fastening these wires to telephone poles. In our combat situation you laid the wire down the side of the road as fast as you could without breaking it. It was important to keep a steady pace since the Germans had the roads targeted with their mortars and shot at any vehicle that moved. Normally it was safer to run the lines at night. Darkness gave you better odds for success. But this night, with a full moon and no wind, you could see and hear for miles.

John Campbell and I hooked up the new wire to the switchboard and joined Bill Everett in the jeep. “Just keep it going fast and smooth,” John said to Bill as we climbed into the jeep for the start of the run.

We moved through the streets of Simmerath quickly making certain that the wire was not getting hung up on roadside debris. We quickly cleared “88 Corner”, so named because the intersection of several roads had been zeroed in by German tanks and artillery. G Company was located about three miles up the road that ran along the crest of a small ridge. I felt as though we were like moving ducks in a carnival shooting gallery.

A mile out of town my fears became reality. German mortars began laying down fire on the road. The first rounds dropped several hundred yards short of us. The second batch cratered the side of the road a hundred yards ahead. It was the third round that landed in the center of the road within 50 yards that brought our jeep to a halt. Everett leaped out shouting, “Take cover!!” I hit the ditch on the left side of the road and Campbell and Everett took the right. A shell landed directly behind the jeep in the center of the road and threw shrapnel and icy clogs of dirt into the air. Something struck me in the middle of the back, momentarily taking my breath away. I reached back expecting to find a bloody wound. Only frozen mud.

“You guys okay?” I yelled.

“Yeah,” said Everett.

“John? You alright?”

There was a long pause.

“I’m okay.” Another pause. “But I’m looking up the asshole of a dead horse.” It was one of the horses the Germans used to haul some of their equipment; they left the carcasses of the dead animals lying where they fell. Fortunately for Campbell the carcass posed no problems in the dead of winter.

The shelling stopped --- we never learned why. The jeep was fine except for a few shrapnel holes in the side and the wire reel was intact. We completed the run and reestablished phone contact with G Company.

Less than a week later, the Battle of the Bulge began just south of our position. For all of December and most of January we spent in defensive positions and by January 30, the Bulge had been flattened and we began our march east to the Rhine River. The going was tough and bloody. Resistance was intense. Towns like Kesternich were heavily mined and ringed with barbed wire. German armor was everywhere. We lost a lot of men on the snow-covered terrain. But the enemy lost more.

~~~ John R Finnegan Sr. ~~~

1924 - † May 7, 2012

Thanks to John for his kind permission to allow me to repost an extract of his wartime story.

Source: finnfamchronicles.blogspot.com