308th Field Artillery Battalion, 78th Infantry Division

Excerpt of Alvin W. Morland's Memoirs

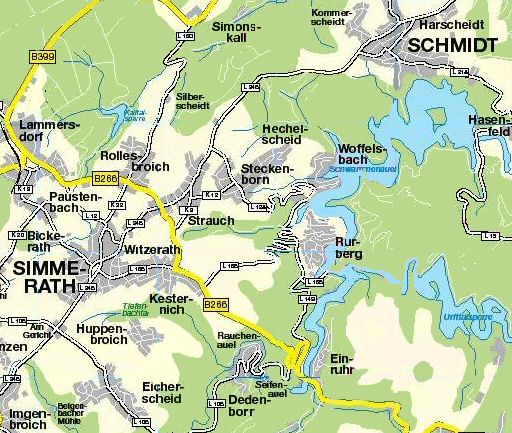

In early December 1944 the 78th Infantry Division was ordered to take a position on the Belgian-German border near Roetgen and prepare to attack. I was a captain in the 308th Field Artillery Battalion, one of four artillery battalions in the Division. The 308th, under the command of Lt. Col. Gregory Higgins, was assigned to provide artillery support to the 309th Infantry Regiment. Based on our training in the U.S., I considered Col. Higgins a highly competent officer and was glad to be going into combat under his command. As we neared the town of Roetgen, we could see flames from fires in the ancient city of Aachen glowing in the distance. The 308th FA set up headquarters in Lammersdorf, a village in the Hurtgen Forest near Roetgen. The 8th Infantry Division was on our left (north) flank and the 2nd Infantry Division on our right. A gap between the 78th and the 2nd was filled by roving patrols from the 102nd Cavalry Group.

THE 78's MISSION

The 78th Division's mission was to attack through the Siegfried Line and secure the Schwammenauel Dam, largest of the dams on the northward-flowing Roer River, before the Germans could blow it up. If they did it would flood the area to the north. Elements of the U.S. Ninth and First Armies were to cross the river north of the dam and its destruction would make the crossing more difficult. A church steeple in the town provided a good observation point, so Sgt. Bob Goldman and I climbed a rickety ladder in the steeple to take a look at the enemy-held territory where we would attack.

THE SIEGFRIED LINE

The ground sloped gently into a draw with the vaunted Siegfried Line stretched across it. In his book, Hell-On-Wheels Surgeon, Dr. John Erbes describes the Siegfried Line as follows.

. . . "the Siegfried line made up of several rows of steel-reinforced concrete blocks that resembled tall pyramids. They measured six or seven feet thick at the base and tapered up like an obelisk tower to a height of about four feet. They were protected by German pillboxes, also of concrete reinforced with steel. The walls were six feet or so thick. The pillboxes had two or more gun ports through which they could shoot with antitank guns, machine guns, or small arms. The pillboxes were situated so that they could observe the pillars of the Siegfried line as well as two other pillboxes, so that the pillboxes had no blind sides.

"Behind the pillboxes the enemy had dispersed tanks and tank destroyer guns that could be moved along ditches to places where the enemy (us) might be trying to break through.

"In addition to the Siegfried line and the supporting tanks and antitank guns behind them, the Germans had their mobile artillery in the rear from which they could concentrate fire on any Siegfried line breakthrough. "I sometimes think that ignorance is bliss, because if we had realized what we were up against, we might have packed up and gone home. . ." (p. 149)

When an attack on the Siegfried line appeared imminent, tanks and tank destroyer guns were dispersed behind the lines, and artillery positioned to concentrate fire on any breakthrough.

Snow covered the road leading to the Line, and we could see only a few of the pill boxes on the far side of the dragon's teeth, but we knew there were plenty of them. A church steeple protruded above the trees in the village of Simmerath, our first objective.

A deathly silence hung in the air - a harbinger of the deaths that would take place when we attacked. A light snow began to fall obscuring our vision, so we climbed down from the steeple. Our feet made crunching sounds in the snow as we walked to our jeep, and I hoped the noise wouldn't alert the enemy when we launched an attack.

That evening I went to my battalion Command Post (CP) in a dimly lit basement in a house in Lammersdorf and was given maps, radio code, and an overlay with numbered concentrations (predesignated targets).

The Siegfried Line on the German-Belgium border

(Revisited by Alvin in the summer of 1945).

PREPARING FOR COMBAT

At 2300 hours (11 p.m.), I took my liaison section consisting of Sgt. Bob Goldman, Cpl. Fred Sommerhalter, Technicians 5th Grade Clayton Agee and J. R. Cupp (radio operator), and Private First Class Ed Deeb, and started out in our two jeeps for Pastenbach, a small village where the 1st Battalion of the 309th Infantry Regiment, the unit which my battalion supported, had set up its CP.

Its commanding officer was Lt. Col. Robert Schellman, a young West Pointer, who impressed me as extremely capable. My job was to advise him on the use of artillery support, to maintain control with the fire direction center of my battalion (Bn FDC), to coordinate the work of the artillery forward observers (FOs), and to direct fire on targets when I was in a better position to see the targets than our forward observers or those in observation planes (Piper Cubs).

We started to set up our radio in a house overlooking Simmerath, but some men from the 102nd Calvary Group warned against it. They said they used it as an observation post (OP) during the day, but withdrew at night after setting booby traps because German patrols often entered the area after dark.

We were convinced and set our radio in a house about 200 yards farther from the enemy. We then laid a telephone line to our FDC, heated some canned food, and tried to get some sleep. Sgt. Goldman slept with radio receiver at his ear.

ATTACK ON SIMMERATH

Before dawn the next morning I set out walking to the Infantry C.P. I started to go through a hedge when someone called out, "Don't go through there." I stopped and one of the 102 Calvary sentries said they had booby trapped the passage through the hedge and it hadn't been removed. He cleared it and I continued on, stumbling through holes and over telephone wires until we found the wirehead. We tied into it and set up our radio.

Even though no snow was falling visibility was limited to less than 100 yards. In the field beside the house the frozen bodies of two cows killed by artillery or mortar fire, lay on their backs, legs sticking straight up in the air.

Radio silence was in effect, but we had permission to break the silence if our FOs called for artillery support. An hour dragged by without any sounds of battle. Suddenly we heard the sharp crack of rifle and machine gun fire and the thud of mortar shells exploding. Then silence. My Bn CP kept calling for information but I didn't have any to give them.

About 10:30 my radio began to crackle calling "14," my code number. "This is 13 (code name for Lt. Norman Schofield, FO with B Co.). Don't fire Concentration 827. Our doughs are all over the place. Get some medics out here - some of them are in pretty bad shape."

"Can you observe Concentration 827?"

"No, I've been hit in both legs and I'm lying flat on my back in the snow. Can't observe anything."

"Are your wounds serious?"

"Negative, but some of these guys are in bad shape. Get some medics out here quick."

This was the first we knew that our troops were on the outskirts of Simmerath and I reported it to Col. Schellman. He radioed Col. Ondrick, the regimental commander, who said he would commit his reserves, the 2nd Bn, 310th Inf, at noon and they would take medics with them. I radioed Lt. Schofield that help was on the way.

Early that afternoon the heavy fog began to lift slightly and we could see our infantry moving across open ground toward Simmerath. At 1500 hrs (3 p.m.) Col. Schellman told us to get ready to walk to Simmerath as it was far too dangerous to take the jeeps. Sgt. Goldman and I decided to take T/5 Culp, the radio operator, with us and instructed Cpl. Sommerhalter, T/5 Agee and PFC Deeb we would let them know when they could bring the jeeps.

Just before we moved out we heard rifle fire and someone reported that snipers had located us. Some of our men fired at locations where the snipers could be hiding, and the sniping stopped.

An hour later Col. Schellman ordered us to leave one at a time, running a zigzag course until we were behind the embankment on the far side of the road. When all of us reached it, he told us to walk in single file so we would look like a patrol and not a command group.

Col. Schellman set a fast pace as he was carrying only a map case and his .45, but it was rough going for my liaison section as we had to carry our radio (an SCR 610) as well as our small arms and knapsacks. The radio was built to be broken down into two sections, each weighing 30 - 35 pounds, and we took turns carrying them.

ENTERING SIMMERATH

When we neared Simmerath someone shouted "hit the ground!" We needed no urging. A short time later word was passed back that snipers were firing at some troops just ahead of us. We were glad to have a chance to rest even though we had to lie in the snow without our overcoats as we had to leave them in the jeeps.

About 15 minutes later the order came to move on. It was getting dark, making the going even tougher. Suddenly we had to hit the ground again. I heard Col. Schellman calling for me and I ran a zigzag course to the him. He wanted to know if I could contact our FO (forward observer) in Simmerath. We set up the radio but couldn't reach him.

We lay on the ground almost an hour before the order came to move into Simmerath. Daylight was fading rapidly, casting an eerie light over the village, and we advanced cautiously, knowing we could be hit by sniper fire, artillery, or mortar fire at any moment.

Col. Schellman's aide located a suitable CP, a 2-story house with a fairly large basement. The infantry CP took up all the space in the basement so I set up my section in a room on the first floor. Our room was far more exposed to enemy fire, but we had no choice as my liaison section and radio had to be available to the infantry commander at all times.

Someone found some blankets in the house and we grabbed two of them. They were our only protection from the near zero cold when we tried to get some sleep.

The house had been hit by shells that left several gaping holes in the walls and in the floor. Frigid winds poured through these holes. A potbellied stove stood in a corner with some charcoal briquettes nearby.

We set up our radio and I reported our position by map coordinates to Bn Hq. I was told a wirehead had been laid to about 500 yards from Simmerath, and we were to tie into it. We had some difficulty finding the wirehead in the gathering darkness but managed to locate it and tie into it. It was none too soon for calls for artillery support began coming in from two of the three rifle companies in the battalion we were supporting.

I was puzzled that no requests for artillery support had been received from the other rifle company. Later I learned that when the company began receiving fire our forward observer became frightened and lost the hand mike to his radio and his maps. He was replaced and sent to the rear for psychiatric treatment.

THE GERMANS COUNTERATTACK

The Germans began shelling Simmerath, and for the first time I learned what it was like to be on the receiving end of artillery fire. In training I had spent many hours at the guns and at observation posts directing fire on targets in the impact area. At the gun positions, there was a boom as shells were fired and then the spotters would radio or telephone where the shells landed in relation to the target.

When I was at an observation post the shells would make a whooshing sound similar to that of a not-too-distant freight train as it rounded a bend. A few moments later a cloud of dust and smoke would appear in the target area as shells hit the ground, and then we would hear the sound of them exploding.

This is the way Marine Corporal Eugene Sledge described being under artillery fire:

"To be under a barrage or prolonged shelling magnified all the terrible physical and emotional effects of one shell. To me, artillery was an invention of hell. The onrushing whistle and scream of the big steel packages of destruction was the pinnacle of the violent fury and the embodiment of pent-up evil. It was the essence of violence and of man's inhumanity to man . . ."

A scale built into field glasses enabled the observer to measure the distance in millimeters the shells hit from the target, and the fire direction center converted this information into commands and relayed it to the guns.

We continued to relay fire commands to our FDC as shells fell around us. It wasn't long before the shells cut our telephone lines, forcing us to rely on the radio for communication with the FDC. As soon as there was a break in the firing, Sgt. Goldman took two men and went out to repair the lines, but they were cut again when the shelling resumed. We continued firing missions by radio whenever Col. Schellman or one of his company commanders requested it.

At about 1 a.m. we lay down on the floor on top of one of the blankets we had found in the house and covered ourselves with the other. This was the best we could do as it was too dangerous to bring the jeeps with our bedrolls and overcoats to Simmerath. Goldman tried to sleep with the radio at his ear, but the bitter cold and shells bursting close by made it difficult to get much rest.

DAY TWO IN SIMMERATH

Just before dawn I was awakened by a GI who said Col. Schellman wanted me. I went down into the basement and saw the colonel bending over a map. He pointed to some suspected mortar positions and asked me to shell them. I relayed the map coordinates to our fire direction center. He then requested fire on other targets.

Meanwhile, enemy artillery and mortar shells continued to pound our position, almost every barrage killing or wounding some of our men. Once I had to chase away an enemy patrol by firing shells just in front of the foxholes of our men. One night I had to call artillery fire within one or two hundred yards of us, adjusting it by sound. This was dangerous but under the circumstances it was the only thing I could do.

The cold was becoming unbearable so we decided to build a fire in the stove and take a chance on the enemy seeing smoke coming from the chimney. Doughboys and tankers felt the warm air when they passed the room to report to the CP and some asked if they could come in. We didn't have the heart to refuse and soon the room was crowded with GIs. There was no place for one of them to lie down so he napped sitting on a box by the stove.

On several occasions prisoners were brought into Simmerath and questioned before being sent to the rear. One night two PWs who walked into our lines and surrendered were brought into my room. They said they had been rushed from Berlin when we attacked, and had little food, inadequate equipment, and only 1,000 rounds of ammunition for each machine gun. They pointed out the location of their regimental CP and some artillery positions on a map. We forwarded the information to our intelligence officers for evaluation.

The next morning Capt. Nelson, a chemical warfare officer, and his two men came to see me to arrange a code and maps in order to coordinate fires of his chemical warfare Bn with artillery. The chemical mortars were being used as heavy mortars, firing explosive shells instead of chemical shells. As they were leaving to return to their jeep I called the captain back for further clarification of the codes. This probably saved his life for a shell landed by his jeep, killing one of his men.

In addition to the constant shelling we also had the problem of snipers sneaking into Simmerath under cover of darkness. To combat this problem, our patrols entered every building as soon as it was daylight to make sure no snipers had sneaked into them during the night.

Our men fired at suspected sniper positions, and once I saw a GI firing armor-piercing ammunition at a brick chimney until he whittled it in two. Another GI kept firing a 57mm anti-tank gun at the upper part of a church steeple reducing it to rubble. A jeep driver from Bn Hq told us Col. Thomas Regan, our division chaplain, had been killed when a shell fragment struck him in the throat. The chaplain was going to aid a wounded GI when he was hit.

The only thing we had to eat since beginning the attack was the canned GI food we carried in our knapsacks. One night we received word that a chow truck had made it to Simmerath with some hot food. We took turns going to the nearby house where the food was. I crawled through an open window to get into the basement and got a hot pork chop between two slices of bread. I didn't know such a simple sandwich could taste so good.

By this time I realized it wasn't possible to keep telephone communications with the fire direction center. Tanks always drew artillery fire as they clanked along and if we strung the lines on poles or trees incoming shells would cut them. If we laid the wire in a ditch beside the road the tanks would chew them up as they swerved around a bend.

Our radio (an SCR 610) was not too reliable so I asked my Bn Cmdr to add a radio technician to my section. He sent one to us and from then on we didn't have to rely solely on the telephone to maintain communication with FDC.

A REAL HERO

Meanwhile, the battle for Kesternich raged. The 2nd Bn of the 310th Infantry was able to get into one end of the village, but on Dec. 15 the Germans counterattacked in force using tanks and flame throwers. The Bn suffered tremendous casualties, and had to withdraw.

Col. Schellman sent one of his rifle companies to help the 310th. I was with the colonel when the company commander, Lt. Jeff Sherman, was called to Bn Hq., and told to move his men to the new line and dig in. "Colonel, " Sherman said, "I'll move my men to the line, and we'll stay there. But they are too exhausted to dig foxholes in this frozen ground."

Exhaustion was written on Sherman's dirty, stubble-covered face and in his every move. When he left the CP I took him by the arm and led him to my room. "If ever I saw a man who needed a drink, you are the one," and poured him a drink from the bottle of Irish whiskey I brought from England. His look of gratitude was one of the best thanks I have ever received.

Sherman's men fought well and orders for his promotion to captain arrived a few days later. Unfortunately he was killed before they arrived.

One instance worth mentioning involves Col. Tom Hayes, a West Point graduate who commanded the 311th Infantry Regiment. Many West Pointers weren't liked by their men, but Hayes was an exception. In one instance one of his men was issued a new pair of boots. When the soldier tried on the boots, Col. Hayes bent down and felt the sides and toes to make sure they fit - an unheard of procedure involving a West Pointer.

One day Capt. Bill Schuler, an aide to Gen. Parker, came into Col. Hayes headquarters in the cellar of a farm house, saluted smartly, and said, "Sir, Capt. Schuler reporting as ordered by Gen. Parker. We couldn't help noticing in contrast with those of us who had been in direct contact with the enemy, Schuler's uniform was clean, his slacks still had a crease, and his boots were polished.

Hayes was hunched over a map under a Coleman lantern, the only source of illumination.

"Whadda ya want, Bill?" he asked without bothering to return the salute.

"Sir, I am ordered to mark the locations of your men's foxholes on a map and bring it to the General."

"OK, the situation map is on the wall. Take them off of it."

"But, sir, I am to go to the foxholes and spot the locations on my map."

For the first time Schuler got the colonel's attention. He took off his steel helmet and looked up at Schuler with bloodshot eyes.

"You do and you'll get your goddamn ass shot off."

Schuler didn't say anything but took the information off the situation map, and made a hasty exit.

Battle of the Bulge

In his book, The Battle of the Bulge, Danny Parker described the situation immediately prior to this famous battle:

". . . By December 13th, the 272nd Volks Grenadier Division [the northernmost division of a fortified line to fend off a U. S. counterattack against the right flank of the Sixth Panzer Army] was itself under attack by Maj. Gen. Edwin P. Parker's newly arrived U.S. 78th Division. The Americans were fighting to capture Kesternich some seven miles northeast of Monschau. The costly house-to-house combat for this gloomy little village surged back and forth inconclusively for days. As a consequence . . . the 272nd provided little assistance for the Germans in their fight for the corner at Monschau [the area through which the German offensive was planned]. Konig, who had just taken over the 272nd, had his hands full with the U. S. 78th Division."

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Hampton Reagan

May 17, 1909 - † December 18, 1944

Thomas Hampton Reagan is buried at

Plot B Row 15 Grave 4, Henri-Chapelle

American Cemetery Belgium.

One of the men from BnHq told us Lt. Col. Thomas Reagan, our division chaplain, had been killed when a shell fragment struck him in the throat. The chaplain was going to aid a wounded GI when he was hit.

The only thing we had to eat since beginning the attack was the canned GI food we carried in our knapsacks. One night we received word that a chow truck had made it to Simmerath with some hot food. We took turns going to the nearby house where the food was. I crawled through an open window in the basement and got a hot pork chop between two slices of bread. Never knew such a simple sandwich could taste so good.

By this time I realized it wasn't possible to keep telephone communications with the fire direction center. Tanks always drew artillery fire as they clanked along and if we strung the lines on poles or trees incoming shells would cut them. If we laid the wire in a ditch beside the road the tanks would chew them up as they swerved around a bend.

Our radio (an SCR 610) was not too reliable so I asked my Bn Cmdr to add a radio technician to my section. He sent one to us and from then on we didn't have to rely solely on the telephone to maintain communication with the FDC.

The enemy shelling of our position in Simmerath intensified, and we suffered some casualties in every barrage. We had no way of knowing it but it was preparation for the last gasp offensive launched by the Germans that came to be known as the "Battle of the Bulge." Later it was described as the largest pitched battle on the Western Front in World War II, and one of the greatest military campaigns in history.

Dense fog prevented our airplanes from observing the huge number of troops and tanks into position to attack the Allied lines. To cover the sound of tanks and troops movements, the Germans flew their planes low over the forces moving forward.

The massive assault began at 5;30 a.m., Dec. 16, 1944, with the Germans firing a tremendous artillery barrage all along the 85-mile front in the Ardennes. The barrage continued for 30 minutes, and when it lifted 250,000 Germans attacked Allied lines with 2,567 tanks and assault guns. The first wave of the attackers was clad in white so they would be difficult to detect against the background of snow.

On December 16 the artillery barrages on Simmerath increased in frequency and duration. We had no way of knowing it but it was the first day of the Battle of the Bulge, and my division's position turned out to be its north shoulder. It was reported that German paratroopers had been dropped behind our lines and to be prepared.

Service batteries in a artillery battalion were usually positioned a few miles back of the front lines to reduce the likelihood of being captured or hit by artillery. All units were on the alert to guard against an attack by paratroopers although only one unit had actually been dropped behind Allied lines.

The call to be alert for paratroopers, however. One incident involving the service battery of my Bn (308th FA) is worth recording. It happened when one of the soldiers standing guard in the woods surrounding the battery heard a sound he thought could have been made by enemy paratroopers. He pulled the glove off his right hand, pulled the pin, and waited. (The grenade will not explode as long as the lever on its side is held down, but six seconds after the lever is released the grenade will explode).

He knew he couldn't hold the lever down but a short time and when he realized the sound he heard was made by snow-laden branches rubbing against each other he tried to replace the pin. He couldn't do it so he threw the grenade as far as he could. Unfortunately, it hit a tree and bounced back toward him. He hit the ground just before the grenade exploded. Luckily, he wasn't seriously hurt but his wounds required medical treatment so he made his way to the aid station.

He was afraid he would be punished if he told the truth so he said paratroopers wounded him. The battery commander ordered everyone out of their sleeping bags and sent them through the woods looking for paratroopers. Meanwhile, the soldier was questioned until he admitted the truth. The commander knew the soldiers would be furious at being rousted from their beds and sent through the forest in search of enemy soldiers who weren't there, so he immediately had him transferred to another unit before they had an opportunity to get revenge.

WOUNDED IN ACTION

The intense shelling continued and I decided to try to locate likely positions of the German artillery and direct fire on them. I timed the interval between the shellings and figured the methodical Germans were following a definite pattern. The next time there was a lull in the firing I sent my wire crew to repair our lines, and I went to try to determine the line the shells were coming from. We were taught to do this at artillery school by taking a back azimuth on the direction marks made on the ground by incoming shells.

When I went outside I saw a medic lying on the ground where he been killed. Fresh blood stains discolored the snow by his body and shell fragments were scattered around shell holes.

I picked up some of the shell fragments, put them in a helmet discarded by a German soldier when he surrendered, and with the help of a GI lined up two sticks with the "V" pattern in the snow the shell made when it landed. The shell fragments indicted the caliber of artillery the enemy was firing, plus an indication of the range from which they were being fired.

I leveled my compass along the line of the sticks to take a compass reading on the direction from which the shells were coming. But before I could get one shells started exploding all around me. All I could do was hit the ground, and as I did I felt a sharp sting in the calf of my right leg. I lay there a few moments and looked around for some kind of shelter as I knew I couldn't survive in this exposed position. I spotted an outhouse a few yards away and ran to it as fast as I could, diving behind it as more shells pummeled the area.

GETTING TO THE AID STATION

When the shelling lifted I hobbled to an aid station in the cellar of a farmhouse, ducking behind whatever shelter was available along the way. Some soldiers had crowded into it seeking shelter, and I hopped down the stairs past them to get to the cellar.

I told an aid man I had been hit in the calf of my right leg, he gave me a tetanus shot, then removed my boot and slit my trousers leg to get at the wound. After working on it a few moments he said, "Here's a souvenir for you," and handed me a shell fragment about the size of the end of my little finger. It had gone through my leg and a piece of my bloody underwear was on it, but fortunately it didn't hit the bone.

I heard Cpl. Sommerhalter's voice in another part of the basement and was told he had been wounded in the buttocks. Sommerhalter was one of the men I had sent to repair our telephone lines and he was caught in the same barrage as I was. The soldier who was changing a tire on a jeep in front of the infantry CP had also been hit.

~~~ Alvin W. Morland ~~~

July 29, 1914 - † July 15, 2002

© Copyright 2002

LEGAL NOTICE

All material on this page is the copyright of Alvin W. Morland, all rights are reserved.

You may download or retrieve materials of this webpage for your own personal use, but not for any other purpose. You may not copy, modify, publish, broadcast, adopt, amend or distribute any of this material without prior written permission of the copyright holder.

Source: One Man's War by Alvin W. Morland, Major

Submitted by his son Douglas Verne Morland

Many thanks Douglas for your kind permission in letting me copy part of your dad's memoirs.