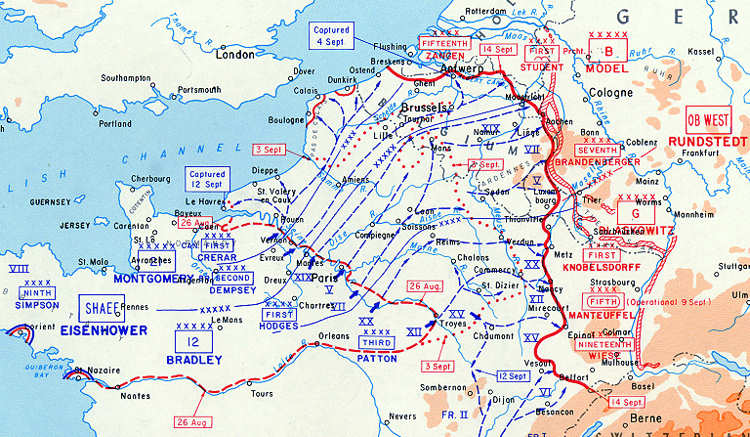

Following the successful landings on the beaches of Normandy on 6 June 1944, the Allies slowly but relentlessly fought their way inland to expand the beachhead. Then on 25 July, after a paralyzing air bombardment, the U.S. First Army launched the attack southward to break out. Joining the assault a few days later, the U.S. Third Army on the right flank thrust southward along the coast while the British and Canadians advanced on the left flank.

When the breakout occurred, Allied planners had expected the enemy to withdraw and reestablish a defense at the line of the Seine River to the northeast. Instead, the enemy launched a powerful counterattack in an attempt to split the Allied forces and isolate the U.S. Third Army. Resisting vigorously, Allied ground and air forces not only stopped the attacking enemy but threatened him with complete encirclement. Thoroughly defeated after suffering great losses, the enemy beat a hasty retreat across the Seine River.

Rapid exploitation of this victory resulted in swift Allied advances far exceeding expectations. On the left flank, the Canadian First Army drove along the coast reaching the Netherlands frontier and liberating Ostend and Bruges early in September, while the British Second Army advanced rapidly through central Belgium liberating Brussels on 3 September and Antwerp the following day. The British Second Army then moved to join with the Canadian First Army astride the Netherlands frontier.

In the center of the advance, the U.S. First Army freed Liege in eastern Belgium on 8 September and continued northeastward toward the German city of Aachen, while at the same time liberating Luxembourg. On the right, the U.S. Third Army swept across France to reach the Moselle River and make contact with the troops of the U.S. Seventh Army advancing from the beaches of southern France, where they had landed on 15 August.

Allied advance through France.

Patrols of the U.S. First Army crossed the German frontier in the Ardennes area on 11 September. The next day, elements of the U.S. First Army crossed the frontier near Aachen and moved eastward toward the Siegfried Line, where strong resistance was encountered immediately. Almost simultaneously, progress slowed all along the advancing Allied line as opposition stiffened. The retreating enemy had at last stabilized its line of defense.

The Siegfried Line formed the core of resistance at the center of the enemy defenses. To the south in front of the U.S. Third and Seventh Armies, and the French First Army which extended Allied lines to the Swiss border, resistance was organized around heavily fortified cities forming strongpoints in front of the Siegfried Line. In the north, the defenders utilized to advantage against the British and Canadians the barriers formed by the extensive canal and river systems. On 17 September, a valiant combined airborne-ground assault in the Netherlands intended to outflank the north end of the enemy line, achieved only partial success as it failed to seize crossings of the lower Rhine.

For the next three months, intensive fighting produced only limited gains against fierce opposition. During this period, the principal Allied offensive effort was concentrated in the center of the enemy line where some of the most bitter fighting of the war occurred in the battle to capture the city of Aachen, the first large German city to be captured by the Allies, and penetrate the Siegfried Line. Finally, encircled in mid-October after savage house-to-house fighting, Aachen fell on 21 October. Meanwhile, the U.S. Ninth Army organized at Brest in Brittany, moved into the lines on the right flank of the U.S. First Army. To the south, the U.S. Third and Seventh Armies continued to advance slowly, as the U.S. Seventh Army forced the enemy back into the Vosges Mountains.

On 4 November, the U.S. First Army began the difficult struggle through the dense woods of the Hurtgen Forest. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. Ninth Army was shifted to the U.S. First Army's left flank. Then, on 16 November preceded by a massive air bombardment, the two armies attacked together opening a wide gap in the Siegfried Line. By 1 December, the Roer River line was reached. On the right, the city of Metz was captured by the U.S. Third Army on 22 November, although the last fort defending that city did not surrender until 13 December. The greatest territorial gains, however, came in the south where the U.S. Seventh Army penetrated the Vosges Mountains to liberate the city of Strasbourg on 23 November as French troops on the extreme right flank liberated Mulhouse.

The Schelde estuary was finally cleared of the enemy by the Canadian First Army and the great port city of Antwerp became available on 28 November to supply the Allied armies.

Suddenly on 16 December 1944, the Allied advance was interrupted when the enemy launched in the Ardennes its final major counter offensive of the war, with a second major assault on New Year's Eve in Alsace to the south. After furious fighting in bitterly cold weather these last enemy onslaughts were halted and the lost ground regained The Allies then developed their plan for final victory.

The first step of the plan was to clear all enemy from west of the Rhine; the subsequent step was to invade Germany itself. During February and March, with the aid and assistance of fighters and medium bombers, the first step was successfully completed and heavy losses were inflicted on the enemy. Because of those losses, the subsequent crossing of the Rhine did not meet with the violent opposition that had beer anticipated. Working together, Allied ground and air forces swept victoriously across Germany, bringing the war in Europe to a conclusion on 8 May 1945.

Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery and Memorial (Belgium).