Timeframe: 01/30/1945 - 02/10/1945

Excerpt from the Personal Memoirs of General Frank Camm Jr.

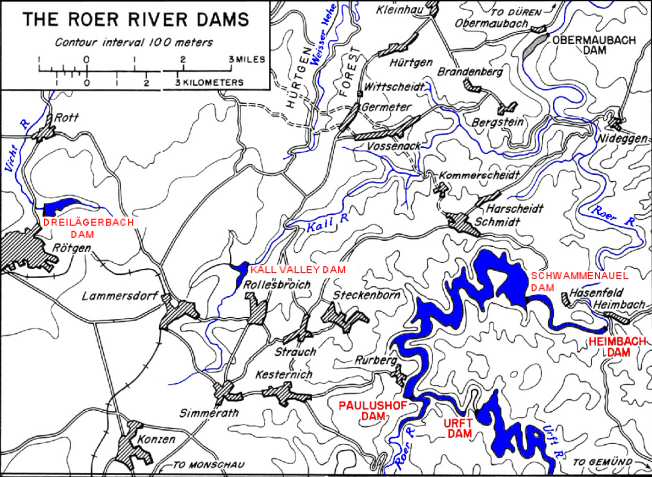

When the Germans had been pushed back from the Bulge, it was time for our 78th Division to attack again. Our goal was still to seize the Schammenauel Dam and prevent the Germans from blowing it to flood valleys downstream, blocking further advance of Allied forces in the north. The 310th and 311th would start the attack to clear our south flank while the 309th would hold in the north, prepared to repel counterattacks. Our combat engineers would open routes through our minefields and breach through the German mine fields. The snow was still on the ground, about a foot deep, so we issued white snow-capes to our men and built sleds to move heavy loads over the snow.

For several weeks, we had used our engineer bulldozers to clear snow off the roads inside our perimeter around Lammersdorf, Bickerath, and Simmerath. During the night before the attack, we lost six bulldozers to mines clearing routes to the lines of departure. German prisoners captured in the subsequent attack said they'd become so used to hearing our bulldozers clearing snow, which had mistaken our approaching tanks for bulldozers and were surprised when we attacked with tanks!

The 311th drive south of Simmerath began with British flame-throwing tanks from Squadron B, Fife and Forfar Yeomanry at 0525, 30 January in a blizzard that lasted all day. There must have been a platoon of the "crocodile" flame-throwing tanks supporting the 310th and 311th Infantry attacks.

Chrurchill Crocodile Flame_throwing Tank

Our job was to get the tanks through our minefields under the snow. How do you detect and remove mines under a couple of feet of snow? Our mine detectors could only detect with assurance through about one foot of snow, so we were deeply concerned about whether we could get them through our own antitank minefields. Fortunately, my men managed to get the tanks through without incident. Immediately thereafter, the tanks came under fire from German 88 antitank guns that knocked one tank out. We had learned to fear the German 88's greatly, constantly wondering when the next shot would arrive even before we heard its whistle! As our infantry proceeded south into Huppenbroich and Eicherscheid, my soldiers saw a British lieutenant in charge of the British tanks walking across the snow with his swagger stick, but no rifle or pistol, and asked him what he was doing. He yelled back, "I'm taking my 'chawnces' with the rest!" Despite this example of British elan, the Kraut 88's took his "Crocodile" tanks out of the action before any of them could employ their flame-throwers. The Stars and Stripes reported, "White clad doughboys of the 78th Division attacked through waist high snow drifts ripping a two to three mile chunk out of the Siegfried Line within nine hours after a surprise assault in rugged forest country."

The 1st Battalion, 311th Infantry, had to toil through at least two feet of snow and in 20 to 25 mph winds across a large open area to reach Eicherscheid. Meanwhile, a Kraut 88 antitank gun on high ground by the town entrance picked off our tanks like ducks in a shooting alley. Having a terrible time getting the wounded out through the deep snow, some medics used doors as sleds on which to drag out the wounded, many of whose faces were frost bitten on the windward side. When our troops reached the town, they found the Kraut soldier who had been firing the 88 antitank gun draped dead over its breech with his head split open. At 0500 the following morning, the Krauts counterattacked, kicking our infantry out of Eicherscheid briefly until we retook it the next day.

Pak 43/41 88mm German Antitank Gun

The 3rd Battalion, 311th Infantry, attacked Huppenbroich southeast of Simmerath on the other side of the hillside. In trying to clear the narrow winding road into Huppenbroich, our men ran into snow too deep to remove. Meanwhile the infantry got caught in mortar fire, suffered in a number of casualties while inflicting even heavier casualties on the defending Krauts. The battlefield became cluttered with enemy dead in frozen and grotesque postures. Finding it urgent to get the casualties out and to resupply the infantry, we changed our approach -- my farm boy engineers improvised makeshift sleds and used captured German horses to haul them out loaded with casualties and back in loaded with ammunition. This is a beautiful example of engineer initiative in support of the infantry in every way possible -- further evidence of the unbounded ingenuity of the American soldier!

Meanwhile on 30 January, Lieutenant Colonel Richard Keyes' 2nd Battalion, 311th Infantry was driving east through "Little Aachen" (Kesternich), where the Krauts had strengthened their defenses during the past six weeks. Using barbed wire, mines, booby traps, and ingeniously placed machine guns fired by string from adjacent buildings, they stubbornly defended their hundred plus buildings with automatic weapons, rifles and grenades. Many antitank guns and two feet of snow in freezing weather also blocked the way. Keyes' men crawled forward at 0530 through the crunching snow under heavy rifle and burp gun fire. Infantrymen carrying radios deliberately assaulted each house, radioing back house numbers as they advanced. The death toll was high, and countless U.S. casualties were evacuated in bitter cold so low that weapons began to jam and freeze.We lost several tanks to mines and enemy shellfire and one got stuck. The infantry fought through the houses literally from room to room, leaving dead and wounded Krauts behind as they proceeded.

In intense action on 31 January, Sergeant Jonah E. Kelley of Company E of Keyes' 2nd Battalion won the sole Medal of Honor awarded in the 78th Division in World War II. Kelley was a brave and uncompromising squad leader, the first to enter every building his squad assaulted in Kesternich. Time and again his squad attacked windows spewing machine gun bullets. Kelley was wounded in one advance and his squad fell back. Refusing to be evacuated for treatment, Kelley charged the enemy position with machine gun in hand. Hit in the right arm, he continued despite being hit again. Using his left arm, he fired time and again. After killing a number of Krauts, including two snipers, he was killed while rushing an enemy machine gun nest that he had knocked out.Of sixty boys in Kelley's high school class in Keyser, West Virginia, thirteen were killed in action in WWII.

The attack continued throughout 31 January when we lost more tanks. Of fifteen tanks starting in the attack, only eight remained. My engineers were at the East End of Kesternich when Lieutenant Colonel Keyes had difficulty getting his tanks to advance southeast toward Einruhr. When Keyes couldn't reach three Sherman tanks standing in the street with German 88 rounds hitting behind them on his radio, he raced out into the bullet-riddled street, climbed up on the lead tank and tried to get the commander's attention, but the turret was buttoned down. Putting his hands over the driver's slit, Keyes found this didn't work, so he took off his steel helmet and banged it on the turret. When the turret opened slowly, he pointed down the street and shouted something before dashing into a house for safety. All this time, Keyes and the tank were under small arms fire and 88's were landing in the street behind them.

The three tanks moved six feet forward and stopped, going no further. Infuriated, Keyes ran out again to the lead tank and banged on the turret with his helmet. When the turret opened, he took out his .45 pistol, cocked it and stuck it in the tank commander's face as the small arms fire and 88's continued hitting all around. This time the three tanks moved down the road as directed. This story spread like wildfire throughout the division, in which our attached tank destroyer battalion enjoyed much greater respect than our attached tank battalion did. Even though the tank destroyers lacked the overhead cover of tanks, they had larger guns and were more aggressive. We found we had to mollycoddle the tanks, and the infantry had to prod them before they would go forward. In two-and-a-half days of fierce fighting under Colonel Keyes' superb leadership, the doughboys of his battalion had battled from house to house, cellar to cellar and rubble heap to rubble heap. The Stars and Stripes report on the battle aptly referred to Kesternich as "Little Aachen." Their dogged determination resulted in a costly victory that won the battalion a Presidential Citation. Col. Keyes was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his inspiring leadership.

Panoramic view Einruhr- Dedenborn

On 3 February, the 1st Battalion struggled across the upper Roer River to capture Dedenborn where the Roer was swollen by melting snow and rain some thirty-five feet wide and too deep to wade. The water was flowing about fifteen feet per second. Somehow two officers and over thirty men managed to get across. Several drowned and about a third lost their rifles, but the rest went on to kill twenty German soldiers and capture forty-three in seizing the Kraut garrison at Dedenborn. They did this by themselves without help from us engineers. In analyzing why we were not able to help in this urgent stream crossing, I found we had no footbridge or other river crossing equipment on hand and no time to requisition it from Corps.

Our failure to help the infantry at Dedenborn led us to develop another one of our battlefield inventions. Turning again to my trusty motor sergeant, DeFriese, I had him fabricate iron H-frames to support 12-foot planks in quickly assembled footbridges. He made one H-frame for each squad so they could have them conveniently on hand for hasty stream crossing. An H-frame consisted of two vertical 2-inch pipes held together by a 2-foot transom that could slide up and down the pipes. The pipes had small footers to spread their loads on the stream bottom. Holes in the pipes permitted pinning the transom at proper height. We nailed the heavy 12-foot boards spanning between the H-frames together where they overlapped. Ropes held the pipes vertical and rope hand rails steadied men crossing. First Sergeant Glenn Titus passed my instructions to fabricate the H-frames on to Sergeant DeFriese.

During this period, the Air Corps sent a group of pilots to the 78th Division to experience the ground situation. Shortly after we took Kesternich, several of these aviators came forward to see the front line. A lone German tank stood with its turret blown off at eastern end of town, still manned by a headless German soldier. As I moved up the street checking for mines, I saw noticed the aviators walking boldly down the middle of the street in their enticingly warm mukluk boots. Suddenly a stick of enemy mortars came in; making them hit the ditch. I still recall reflecting then on how unfair it was for these "flyboy tourists" to wear so much better protection against the cold than our miserable ground soldiers!

About this time Rip Repinski, an A Company engineer recently promoted to lieutenant on the battlefield, was back on Rest and Recuperation (R and R) from the front. Sitting at a bar, he got into an argument with an air force major. Knowing the pilot led a crew of only two to five men compared to his engineer platoon of 40 men, old Rip looked the major straight in the eye and said, "Major, a lieutenant in the Engineers is equal to a major in the Air Corps!"

As our Division turned north toward Schmidt and Schwammenauel Dam, the cold weather of the two previous months gradually gave way to the mud and slush of early spring, causing the poor roads in the area to collapse under the weight of heavy support weapons, armor, and supplies. Adequate replacements had been received by late January and morale was excellent. On the other side of the line, the Germans were not in so good a position, except for terrain. Naturally, their morale had fallen with the failure of their Ardennes counteroffensive. Their units were under strength and some were but bare remnants of larger units. Allied air activity was causing serious problems in support of their Siegfried Line positions, although they had adequate local stocks on hand. The overall combat efficiency of U.S. forces was excellent and that of the German forces good.

After taking Kesternich, the 311th drove toward Rurberg down in the Roer River valley. Moving in my jeep from Kesternich to Rurberg, I passed the 1st Battalion commander and his staff talking to newspaper correspondents on the side of the road when Kraut artillery shells came crashing in. I learned later that these shells wounded the battalion commander and his A Company commander and killed three enlisted men, two officers, and two war correspondents. With the seizure of Rurberg, the Division was ready for its third and final phase objective, the Schwammenauel Dam on the Roer.

We've moved again and occupy a house partially shattered by artillery fire. Though it cannot keep out rain, the floor is dry and we can "black-out" our room at night. We moved in with an antiaircraft crew, so they are now enjoying our radio and hot chow. This war brings out the good in men who find that selfishness gains them little, but good fellowship and helping the next man pay off big. Here we are taking these fellows in and even supplying them clothes, while they swap with us cognac and yarns about their days in France. (6 Feb 45)

Early in February, newsreels about our 303rd Engineer's demolition of pillboxes in the Siegfried Line appeared on the screens of theaters in the States and London. "Combat Diary" also featured our battalion in one of its "Salutes to the Armed Forces."

On 5 February, V Corps directed the 78th Division to plan for a 311th Infantry task force to cross the Roer during the night of 6-7 February near Rurberg and attack northeast to secure the south end of the Schwammenauel Dam. But the plan was abandoned when reconnaissance supervised by the Assistant Division Commander, Brigadier General John K. Rice, revealed the Roer was too swift for crossing in boats and enemy observation of the entire area from protected concrete pillboxes could inflict frightful casualties. Upon first hearing of this scheme, I had examined the terrain across the Roer and found the routes to the Dam were far too steep and rugged through easily defended dense forests for further consideration. I wonder whether I would be here today if this hare-brained scheme had been implemented with my company providing its usual combat engineer support to the 311th Infantry!

After seizing Rurberg, our regiment drove north toward the key town of Schmidt. (See Taking Schmidt Map on next page.) Numerous pillboxes barred the way to men climbing the wooded hills and crawling up the deep ravines. The area was heavily mined with long rows of Riegel, Teller, and Box antitank mines. Schu-mines and other antipersonnel mines also made the going rough. The Krauts counterattacked regularly, but they were beaten off. Though Woffelsbach, Steckenborn, and Strauch were strongly fortified and manned to protect the approaches to Schmidt, our 311th Infantry captured all three towns by dark on the 5th of February. It was in these operations that we first encountered concrete pillboxes camouflaged as summer cottages. As Lieutenant Colonel Keyes said, "It was a pleasure to watch my men work. One man would make a reconnaissance, then get back to his group. Two men would flank out and open fire with automatic weapons or rifles while another moved in for the kill. The action required about fifteen minutes per pillbox, and the Krauts would come pouring out."

Soon droves of scared and dazed prisoners came streaming back from the front. Our magnificent infantry had blasted all traces of conquering supermen out of them. Meantime, Generals Eisenhower, Bradley and Hodges came into our area to visit General Parker. This was obviously the big push!

At 2230 hours on 6 February, the 3rd Battalion, 311th Infantry received orders to take Schmidt with the help of company A, 774th Tank Battalion. Heading towards Schmidt, they found the sky lit with flashing enemy shells and barrages of artillery and mortars. About a thousand yards from the edge of town, they encountered bitter resistance. Their lead tank was destroyed and the heavy armor pulled back, but the infantry moved in against heavy machine gun fire. Firing machine guns from their hips, the I Company men continued to advance. Kraut gunfire killed many and others died stepping on mines.

Meantime my company received a novel contraption to clear tank mines from the main road into Schmidt. It consisted of a medium tank pushing a pair of huge steel rollers to detonate mines in its path. The four rollers in front of each tank track were about eight feet in diameter and three inches thick. Our men guided this contraption in the dark of night up the road to Schmidt through heavy snow and ice. Suddenly the heavy rollers slid into a ditch and the tank became stuck. This battlefield experiment failed miserably, and we never saw the contraption again.

We became quite adept at detecting enemy mine fields visually along the roads. We'd sit up on a jeep's right front bumper so the driver could see past us on the left while we swept the road and roadsides with our eyes. As combat engineers, we knew the best locations for minefields were generally where they could tie into steep places or other obstacles blocking easy passage around them. Enemy mines buried in our sector had usually been emplaced several months before. As they weathered, they tended to settle into the ground in patterns that we could discern in the grass as we looked across the fields. In the roads, we could detect mines more readily in the pavement. Sitting above a front wheel that would explode any mine it rolled over motivated us mightily to see every mine! Fearful of removing by hand mines that could be booby-trapped, we often tied ropes to the mines and backed off about thirty yards to pull them out. Few did explode.

While riding on my bumper toward Schmidt, I saw the trace of a minefield crossing from one side of the road to another. We stopped the jeep and an infantry jeep halted right behind us. My jeep driver and I were standing beside our jeep looking at the minefield when BAM! I woke up in the ditch with my ears ringing! I felt myself carefully all over to see whether I had been hit. Looking at my jeep driver, Crouse, I asked," How are you?" He said, "I'm all right, Sir--and you?" I replied "I'm okay too!" When we looked up, we saw the infantry jeep behind ours was no longer there.

As we looked around we found an enemy mortar had landed on the far side of the infantry jeep and blasted it over our heads to our side of the road, throwing out its occupants and wounding them badly. Grabbing the two infantrymen, we jumped into our jeep and rushed them to an aid station about a half-mile back. I had a headache, my ears were still ringing, and a little blood was seeping out of one ear. It was about a day before my ears stopped ringing. When I mentioned this some time later an officer asked, "Why didn't you apply for a Purple Heart?" Not looking for any decoration, I was just glad I was still alive in one piece and happy I didn't get a bullet or shell fragment in me! These were what I feared most. However, I did taste what it was like to be knocked out by a mortar. My hearing has never been very good since then, and it's been made worse by exploding demolitions, artillery, and riding around in helicopters--normal hazards of the military profession!

The next day when we drove along the same road, I saw a column of about forty German POWs (Prisoners of War) marching to the rear with a couple of GI guards. Suddenly an incoming shell landed about thirty yards away. The GI guards dropped to the ground for protection, but the Germans just kept right on walking, not even flinching. Those Germans had been under so much of our artillery fire that they knew when it was close and when it wasn't, but their American guards hadn't been under enough to know the difference. Our artillery was always plastering the Krauts. I wouldn't be surprised if we fired twenty to fifty shells for each German one that came in on us.

On 7 February, our regiment's northward drive into the toughly defended stronghold of Schmidt would have made a good movie setting. Having rebuffed a couple of previous American attacks, Schmidt looked like a tank and vehicle graveyard. The bodies of dead Krauts lay all around, some missing ring fingers that scavengers had already reached. Tanks hung over edges of cliffs. Other paraphernalia of broken weapons, occasional overcoats, and cartridge belts remained where their owners had dropped them. Minefields were also there--one large one covered the northwest approach to town. Elements of four German divisions were defending Schmidt--the 85th Infantry, 9th Panzer, 3rd Parachute and 3rd Panzergrenadier. As mortar and artillery fire fell on the town, the 311th doughboys dashed forward, hitting the ground, jumping up for another dash, hitting the ground again, firing as they advanced. Krauts on the far side of Schmidt scurried out of town so fast their overcoats were flying over their heads. Godfrey Stallings in K Company of the 311th Infantry described his company's attack as follows:

My company was to make the main direct assault on this village... Our approach was to be across a wide-open space from the edge of a forest where we were to rendezvous with tanks. Tanks always make a lot of noise when they move with their motors roaring, treads clanking and squeaking...The enemy found out we were in the woods behind the tanks . . . and began a heavy barrage of artillery shells into the woods where we were waiting... Boy! Those artillery shells were knocking down trees, plowing up the ground, and shrapnel from the exploding shells was flying everywhere, causing casualties...I fell down beside a large tree seeking as much protection as possible. A shell cut the top out of that tree ... the top slid down the tree trunk and almost pinned me to the ground. Our captain, realizing we would be cut to pieces if we stayed there, jumped up and started ordering us to move forward out of the woods. We started the attack across the open area on foot ... Everybody seemed to be firing everything they had and I do mean everybody was shooting... We didn't have much protection in the open area. Just blades of grass, weeds, and depressions in the ground left by tank tracks. Our best bet was to keep moving forward. One group would shoot while another group moved forward. They would hit the ground and shoot while another group moved up. It was sort of a leap frog action. When you ran forward, it was a zigzag pattern and when you hit the ground you rolled to spoil the aim of any enemy shooting at you.

When the leading tank got almost to the edge of the village, it was hit by antitank shells and set on fire. Seeing this, the other two tanks wheeled around and started back toward the woods. Seeing the attack faltering, Captain Ferry (my company commander) ordered everybody to start moving toward the village again and kept the attack going. We finally made it to the edge of the village and the house-to-house fighting began... Two of our guys started running toward a house when a hidden machine gun opened up on them. One guy fell to the ground and the other guy dived through an open space that had once been a window or door. Spotting smoke from the machine gun firing at them, he lobbed a hand grenade that took care of the situation. I thought the guy that fell to the ground had been hit, but he had stumbled over a piece of wire that probably saved his life... Whew! What a way to earn $64.80 a month as a private first class plus $10 a month for my Combat Infantry Badge!

Finally our 310th and 311th Infantry regiments gained possession of Schmidt, which had stayed the military might of our allied forces for several months. Some military writers have estimated this town was worth at least five divisions to the enemy.

While the 310th went through Schmidt and on to capture Harscheidt, the 311th moved toward the dam, following the curving north shoreline of the reservoir.

Just after we captured Schmidt, I was ordered to lead a daylight patrol to look for a good site from which to launch assault boats to ferry infantry across the lake behind Schwammenauel Dam on the Roer River. The far side had steep hills occupied by enemy soldiers with good observation on us. A 311th Infantry company took up positions on high ground overlooking my patrol route along the lake south of Schmidt while I took a squad of infantry along for security. We soon found an empty German dugout with a field telephone that had obviously served as a German forward observation post. Ever fearful of running into Krauts, we followed the telephone line to where it went into the lake. We encountered no enemy, but they were obviously over there on the far shore, prevented from shooting us by our overwatching infantry. We came back to report that we could emplace assault boats under cover of night or heavy smoke, and ferry infantry across, but the hills on the far shore would be terribly challenging.

In our drive for the dam, Dad's division artillery was given enormous artillery support from Corps and Army artillery. At one point, he was coordinating the fires of 26 artillery battalions, including 155-mm guns, 8" howitzers, huge 240mm howitzers, and even a British rocket battalion. This concentration of firepower of nearly 300 artillery pieces was one of strongest artillery concentrations in First Army history.

We spent the following night standing by to undertake an assault crossing, but the order never came. Instead, I received instructions to provide a patrol to inspect the Schwammenauel dam once we reached it. We had to be sure that the Germans had not prepared it for demolition to flood the Roer River valley while our forces were in the midst of crossing it downstream. If the Krauts were to blow the dam, an 18-foot wall of water would crash 36 miles down the Roer across our front. Within four hours, this German-made flood would trap any allied forces that had ventured across the Roer into the Cologne Plain. I designated my company executive officer, Lieutenant Maurice Phelan, to organize and lead the patrol. A sharp and reliable officer, Phelan selected Private First Class Pearl Albough, Private First Class Harold Fisher and Private Kenneth Hart from Bill Monroe's 3rd Platoon and Private Kurt Storkel from Glen Timm's 2nd Platoon to accompany him.

About mid-morning on 9 February, radio operator Joe Grimaldi was with the commander of the 1st Battalion, 311th Infantry, when they reached an exposed hilltop overlooking the dam. He reported that as they were watching their troops assault at the hill on their left, a tremendous explosion erupted near the center of the dam, carrying water and debris up several hundred feet. Shortly thereafter, there was a second, lesser explosion on the dam.

As our 311th Infantry reached the final approaches to the dam on the afternoon of 9 February, the 1st Battalion, 309th Infantry passed through them and slogged down the final way to the dam. The shell torn road behind the advancing doughboys was strewn with burned-out tanks, jeeps, wrecked trucks, and dead horses.

The 1st Battalion, 309th Infantry had spent the previous four days preparing for the final assault on the dam. Lieutenant Phelan and his engineer patrol had worked with them, studying aerial photos and blueprints of the dam. Built in 1934, the earthen dam was 188 feet high, 1000 feet long, and 1000 feet thick at its base. Directly under the road leading across the dam was a massive concrete core. Running lengthwise inside this core was an inspection tunnel that we visualized could be packed with demolitions, with the Germans waiting for the opportune moment to press the button and send it sky high.

One hour before midnight, the leading riflemen of the 1st Battalion, 309th broke out of woods at the bottom of a steep hill, and there was the prize -- the Schwammenauel dam! Enemy flares from the far side of the river lighted up the area. Machine gun fire spattered all around. The crash of mortar shells mingled with the whip-cracking reports of flying lead. Registered-in 88's whined over the dam to burst at knee height among the doughboys. As the battalion drove forward to seize the dam, they heard the unmistakable, dull rumble of demolitions. Fortunately, only the valve house exploded -- not the dam itself. Meantime German resistance at the gatehouse was overcome only after the Krauts had succeeded in damaging the intake valves and jamming them in an open position. The damaged intake gates and blown outlet valves indicated a thorough German demolition plan had been executed!

As the firefight raged unabated at 2300 hours, Lieutenant Phelan's patrol started across the four hundred yard exposed roadway atop the Dam. German flares revealed them almost immediately, and machine gun fire from high ground south of the dam drove them back. It seemed every available enemy weapon was aimed at the dam. Phelan later said, "It was like a ten-minute artillery barrage repeated every ten minutes; between shell explosions, we heard the burp-guns." Dad's division artillery had lined up every piece of artillery within range to support seizure of the dam - approximately forty-three battalions of all calibers. Within a few minutes, thirty of these battalions were firing a "time-on-target" concentration. It was truly impressive to watch it hit along the German side of the river. This intense fire covered the area a half mile east and west of the dam and 200 yards inland to the south, momentarily illuminating the river and dam.

Phelan's patrol tried again at midnight. Dashing a thousand feet across the dam through rifle fire and bursting artillery, they found the spillway inaccessible. Sliding down the two hundred-foot face of the dam to a tunnel entrance on the enemy side, they slipped into a six-foot causeway, surprising and capturing six German machine gunners and riflemen. Within a few minutes, the patrol reached the tunnel entrance, and the engineers entered to make their inspection, while the doughboys took up defensive positions at the entrance. Groping their way through the inspection tunnel in the very bowels of the Dam, the engineers knew that an already lighted fuse could be burning closer to a mighty charge. Nervously but quickly, they searched for explosives set to blowup the dam, scouting for wires and fuses, any shred of evidence the dam was mined. It was a ticklish job, but it had to be done. Phelan later told reporters, "We expected to be blown to bits by hidden charges."

Lt. Phelan's patrol returned to the 1st Battalion CP at about 0300 hours. Incredibly and much to everyone's surprise, the dam itself had not been prepared for demolition! The logical place for explosives in the tunnel contained no prepared charges! The Germans had not mined the structure. A bridge across the sluiceway and the control houses on the far side had been demolished. The control to the penstock tunnel was also destroyed, sending a thirteen-foot diameter stream of water gushing out of the reservoir. It would take several days for the Roer River to subside. Schwammenauel dam no longer was a menace to four Allied Armies in the north. Fearful of being engulfed by the eighteen-foot wall of water that the Germans could unleash on them within four hours, these armies had been waiting since November to cross the river.

Meanwhile, Staff Sergeant Ed Naylor from our 303rd Engineer S-2 Intelligence Section led another reconnaissance party with a bomb-disposal sergeant from Army and seven infantrymen to the gatehouse. They blasted its door open with a bazooka and returned about 0400 to confirm that the outlets had been blown and water was rushing into the valley below.

On the following morning, 10 February, the 303rd Engineers dispatched the following message:

"THE GREAT DAM THAT HAS SO LONG IMPEDED ALLIED OFFENSIVES ON THE WESTERN FRONT, HAS NOT, AND WILL NOT, BE BLOWN --

THE OFFENSIVE MAY PROCEED ON SCHEDULE."

By blowing only the valves in the underground flume and keeping the great structure intact, the Germans created sufficient flooding of the Roer River to delay Allied crossings for another two weeks. Had they demolished the dam itself, the flash flood would have lasted only about one day. Thus, the Germans delayed us substantially longer with their partial demolition than they would have if they had blown the full dam.

Following seizure of the dam, Major General C.R. Huebner, V Corps commander, dispatched a commendation to our 78th Division stressing the strategic importance of our accomplishment, "Without which further contemplated operations against the enemy on the northern front would have been impossible... Although the 78th Infantry Division is relatively new in combat, you have given ample proof that in future operations you will add new honors to those you have already achieved in this..."

Panoramic view Schwammenauel Reservoir

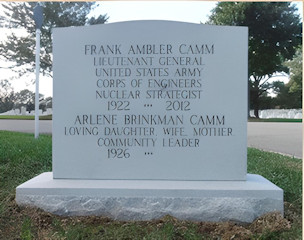

~~~~ Frank Camm ~~~~

March 13, 1922 - † January 17, 2012

Source: The Personal Memoirs of General Frank Camm Jr.

I would like to thank Frank Camm for granting me permission to reproduce this chapter of his memoirs on my web site. Scorpio