Fox Company, 310th Regiment of the 78th Division

As I Recall the War

by Warren Fagerland, Rapid City

February 1943: Greetings from the President of the United States. You are to report for duty March 3, 1943, at Fort Snelling, Minnesota.

Some may say, when you have heard one war story, you have heard them all. My experiences were not that much different from many thousands of others, but this is MY war story, for you to read or not read, as you choose.

At Fort Snelling, we went through the usual screening to determine what branch of service we were best suited for, and since I had experience driving a Cat, they assigned me to the Tank Destroyers and sent me to Camp Hood, Texas. Using the normal military logic, since I could drive a Cat they decided to train me as a radio operator! It was an exciting time for me and I truly enjoyed it. Basic training in the TD's was tough, as tough, they say, as Marine training. We were confined to camp for a month, and when we finally got a pass to the town of Gatesville we found it was as crowded with GI's as the camp. If a girl came in sight we all stared! There were some big name entertainers who came to camp, the Andrews Sisters of "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy" fame, Red Skelton, and of course Bob Hope. Bob always used the routine to call a soldier up to the stage for interview, rehearsed of course. Bob said, "I hear you Tank Destroyers are really tough." "Yea, I guess so." "So how many tanks have you destroyed this week?" "Four or five, I guess". "Tell me, what kind of weapon do you use to destroy a tank?" "You're supposed to use a weapon?"

At Fort Snelling, we went through the usual screening to determine what branch of service we were best suited for, and since I had experience driving a Cat, they assigned me to the Tank Destroyers and sent me to Camp Hood, Texas. Using the normal military logic, since I could drive a Cat they decided to train me as a radio operator! It was an exciting time for me and I truly enjoyed it. Basic training in the TD's was tough, as tough, they say, as Marine training. We were confined to camp for a month, and when we finally got a pass to the town of Gatesville we found it was as crowded with GI's as the camp. If a girl came in sight we all stared! There were some big name entertainers who came to camp, the Andrews Sisters of "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy" fame, Red Skelton, and of course Bob Hope. Bob always used the routine to call a soldier up to the stage for interview, rehearsed of course. Bob said, "I hear you Tank Destroyers are really tough." "Yea, I guess so." "So how many tanks have you destroyed this week?" "Four or five, I guess". "Tell me, what kind of weapon do you use to destroy a tank?" "You're supposed to use a weapon?"

We were trained mainly with halftrack anti-tank vehicles but also trained extensively with machine guns, rifles, grenades and explosives. As most of the other recruits were East Coast city kids I think my background gave me an advantage. I earned my Expert Badges in both rifle and carbine marksmanship, and training came easier for me than some.

After basic we spent another three months in advance training, then again with army logic, they transferred us to the Field Artillery! We were sent to Fort Jackson, South Carolina to develop an eight-inch howitzer unit. A howitzer battery consists of four howitzers, each requiring a seventeen-man crew, consisting of a chief-of-section, gunner, assistant gunner, ammunition corporal, truck driver, and twelve ammo handlers. An eight-inch howitzer fires a two-hundred pound projectile up to seventeen miles and is towed by a two ton truck. After more training I was assigned as the gunner, second in command. Then I was promoted to sergeant, chief of section, and was sent to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, as cadre to train another battery. All went very well until the Battery Commander, an old horse cavalry officer, decided to demote a few of us cadre and promote some of his own choosing. That was a turning point in my army career. I could have transferred to another battery and worked to get my stripes back, but I was angry and depressed and wanted a change.

After basic we spent another three months in advance training, then again with army logic, they transferred us to the Field Artillery! We were sent to Fort Jackson, South Carolina to develop an eight-inch howitzer unit. A howitzer battery consists of four howitzers, each requiring a seventeen-man crew, consisting of a chief-of-section, gunner, assistant gunner, ammunition corporal, truck driver, and twelve ammo handlers. An eight-inch howitzer fires a two-hundred pound projectile up to seventeen miles and is towed by a two ton truck. After more training I was assigned as the gunner, second in command. Then I was promoted to sergeant, chief of section, and was sent to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, as cadre to train another battery. All went very well until the Battery Commander, an old horse cavalry officer, decided to demote a few of us cadre and promote some of his own choosing. That was a turning point in my army career. I could have transferred to another battery and worked to get my stripes back, but I was angry and depressed and wanted a change.

I had been in the army for eighteen months in the States. I decided I wanted to go overseas. First, I volunteered for paratroop service but did not pass my physical due to poor eyesight in one eye. Then I volunteered for overseas duty as an artillery replacement. Foolishly, I thought I would be transferred to another artillery battery overseas. It never occurred to me that the artillery does not have a lot of casualties, so replacements are not often needed. The infantry, on the other hand . . .

The ship I went over on was the Nieuw Amsterdam, a Dutch liner that was converted to a troop ship and operated by the British navy. It was crammed with seasick soldiers and took ten days to cross, going out of the way to avoid submarines. We were glad to get off in Scotland. Then by train to Southampton, England for the trip across the English Channel to Le Havre, France. Crossing the Channel was my first close call. We were on an LST, (landing ship, tank), a small craft. Midway across we struck a floating mine, which was timed to detonate a few seconds after impact, to go off at the weaker stern part of the ship. Being a small craft, we went past it before it blew. The ship rolled over on its side and righted itself again. I was on deck hanging on but very nearly went overboard. We landed at Le Havre late at night on Thanksgiving Day, 1944. The guys that were there before us were served a full turkey dinner. We hadn't eaten all day and were starving but the dinner was all gone when we arrived. We settled for a few scraps. Then we were put on a French train, one of the infamous "Forty and Eight" boxcars that were used in World War One. (Meaning forty men or eight horses. The train kept breaking down and it took two or three days to get one hundred fifty miles to the camp.

The ship I went over on was the Nieuw Amsterdam, a Dutch liner that was converted to a troop ship and operated by the British navy. It was crammed with seasick soldiers and took ten days to cross, going out of the way to avoid submarines. We were glad to get off in Scotland. Then by train to Southampton, England for the trip across the English Channel to Le Havre, France. Crossing the Channel was my first close call. We were on an LST, (landing ship, tank), a small craft. Midway across we struck a floating mine, which was timed to detonate a few seconds after impact, to go off at the weaker stern part of the ship. Being a small craft, we went past it before it blew. The ship rolled over on its side and righted itself again. I was on deck hanging on but very nearly went overboard. We landed at Le Havre late at night on Thanksgiving Day, 1944. The guys that were there before us were served a full turkey dinner. We hadn't eaten all day and were starving but the dinner was all gone when we arrived. We settled for a few scraps. Then we were put on a French train, one of the infamous "Forty and Eight" boxcars that were used in World War One. (Meaning forty men or eight horses. The train kept breaking down and it took two or three days to get one hundred fifty miles to the camp.

About the next three weeks, we spent in a replacement depot in France awaiting transfer to a unit. Then the Germans started their big offensive and the "Battle of the Bulge" begins. There was no longer any doubt where we were going. Everyone in camp was issued an M-1 rifle, we were taken to a rifle range to zero in the sights, and we were in the infantry!

M-1 GARAND RIFLE

Some of us were trucked to a point on the German/Belgian border and I was assigned to F Company of the 310th Regiment of the 78th Infantry Division. We were knee-deep in snow, it was terribly cold, I had no infantry experience, did not even know how to pack my infantry pack, I was depressed and scared. It had to be one of the lowest points of my life.

The make-up of an infantry unit is, each Regiment has three Battalions, each Battalion has three Companies, each Company has three Platoons, each Platoon has three Rifle Squads. The lowest denominator, the Squad, has twelve riflemen when filled. Each rifleman was equipped with an M-1 Garand rifle, a bayonet, an ammunition belt, canteen, mess kit, first aid kit, gas mask, (which we soon discarded), a back pack which held a wool blanket, a shelter half, (half of a two-man pup tent), an entrenching tool, personal belongings and extra socks and underwear. Our clothing consisted of wool socks and underwear, wool shirt, pants and sweater, long wool overcoat, combat boots, four buckle overshoes, mittens and steel helmet. As a general rule, when two parts of a unit are in action, the third is held in reserve or will fill in where needed.

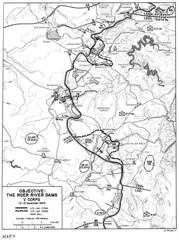

Prior to my joining the outfit, the 78th Division had just recently arrived from the States, and first went into combat on December 13th, 1944. They were based in Belgium and the mission was to capture the German towns of Roetgen, Lammersdorf, Simmerath, Rollesbroich, Kesternich, Schmidt, and the objective was to take the Schwammenauel Dam on the Roer River. To do that they would have to cross the heavily fortified Siegfried Line, with all the pillboxes, bunkers, "dragon's teeth" barriers, not to mention the heavily wooded Hurtgen Forest. There are books written about the battles of the Hurtgen Forest. F Company was to take Kesternich, an important crossroads town. In two days, with heavy casualties, they had gotten a foothold in the town. Unbeknownst to them, they ran smack into the brunt of the German offensive, the beginning of the "Battle of the Bulge".

OBJECTIVE: THE ROER RIVER DAMS

Click for larger image.

Note: This is an external link, clicking it will open a new browser window!

Up until then, the Germans had been retreating and our forces had taken town after town with heavy fighting. Hitler's strategy was to gather all the forces available, with his best tanks and armored divisions and drive a wedge through Belgium to the sea, take Antwerp to have a seaport, divide the allied forces and negotiate a truce. He timed it with a period of bad weather so our air power would be ineffective. He expected to capture our fuel storage tanks in Belgium. It could have worked. He drove a deep "Bulge" into Belgium and Luxembourg before he was stopped at the battle of Bastogne. So much for the history lesson.

During the beginning of the German offensive, there was chaos and confusion on the American side. The Germans had parachuted soldiers who spoke English, dressed in American uniforms, behind our lines. This was strictly against rules of war, and those who were caught were later tried and shot. The Germans also had captured a large supply of our equipment, including Christmas parcels that had not been delivered and were stored in warehouses. Much later, we saw German film of them celebrating, opening our Christmas presents. We were advised at this time to tell our families to not send anything, so of course we did not receive any.

31 Jan 1945 : US 78th Infantry Division soldiers advancing through Kesternich, passing two knocked-out Hetzers among residential ruins.

The main street (Hauptstrasse 80) of Kesternich in 2008.

When the full force of the German offensive hit Kesternich, our forces were driven back with very heavy casualties. A small group of about eight men had taken refuge in the basement of a bombed out house, and in one of the most talked about events of the Battle of the Bulge, held out for six days without food or water, some were wounded, all had frozen feet. They were completely surrounded and taking heavy shelling from our own artillery, as it was not known they were there. Twice they sent out two men to try find their way back to our lines but they did not return. The third time they got someone through and a rescue party went back at night and brought the survivors back. One 78th sergeant (Jonah E. Kelley) received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions in the battle of Kesternich. Out of all the F Company men involved in the battle, only eight men and one officer were able to go on. The Company Commander was also wounded and out of action.

GIs from the 311th Infantry Regiment inside the Village of Kesternich, February 1944.

The same spot today (Hauptstrasse 56) of Kesternich in 2008.

That was the situation when I arrived on the scene as a replacement. We got a new Company Commander, Lt. Bowman, and the ranks were filled by some transfers and mostly replacements like me. F Company was in reserve while getting the ranks filled and we were in a holding position for a time. Luckily, I was not placed in a rifle squad but was assigned the position of Company Runner. Basically I was a rifleman but mainly I was to be available to the Company Commander to bring messages to and from the Battalion Message Center. When we were on the offensive, I was a rifleman with the Company. When we were more or less stabilized I spent more time with the Message Center, which could be anywhere from a hundred yards to half a mile behind the Company lines. As we seldom used radio for fear the enemy could intercept, there were always communications that had to be done by runner. For example, I would bring the new password up front every day. (A new password with countersign was changed every day for the whole front, and you had better not forget it!) I would bring new replacements to the front. (One of my saddest memories are of the two new recruits, fresh from basic training, that I brought up front and heard the next day they were both killed.)

During this time as we were getting reorganized I was assigned a runner partner, Burt Klapper. We were holed up in bombed-out buildings or basements and exchanging artillery shelling. Many close calls as shells would hit within yards of our shelters. Our worst enemy was the cold. It was recorded as the coldest winter in many years with much snow. We were mostly in a holding pattern on the north edge of the "Bulge", as the German offensive had been halted but we were slowly advancing, pushing them back. "Foxholes" as such, were nearly impossible to dig in the deep snow and frozen ground, but shell holes, abandoned buildings or cellars served as shelters. At one time, I think in Lammersdorf, we took shelter in a small church for the night. It was being shelled, but we managed to get some sleep. Imagine our surprise to wake up in the morning to see a small group of German civilians gathered for services. They ignored us and held their services up front while we were gathered in the back of the church.

Every day we would watch our bombers go over by the hundreds on the way to the German cities. We would also see and hear the German V1 and V2 rockets go over on the way to Liege, Belgium or London and other English cities. In our war, there was little effort to spare civilians. The objective on both sides was to destroy the enemy cities, and destroyed they were. The original V1 rockets were no more than flying bombs. They were not accurately targeted except by the amount of fuel that they carried. They were directed toward the target and when the fuel was gone, they dropped. They sounded like a the small engines used on wash machines of the time and we called them "Maytags".

My first real combat action. I will quote a chapter taken from the official Company F Combat Diary: "It wasn't too long before we got another crack at the enemy, for at 0530 the 30th of January, the company made an attack two miles east of Konzen, Germany. Plowing through waist-deep snowdrifts and loaded down with bandoleers, hand grenades, satchel charges, and rocket shells, the men struggled on. Every man was outfitted in a white snowsuit at the time of the jump-off, but they were soon so tattered and torn they were discarded. The action was swift and strong. Four British Churchill tanks, equipped with flame-throwers were attached to our company, but these were knocked out by mines at the first encounter. Undaunted, the men pushed on. About 1000 hours a roaring blizzard set in, and nearly every rifle and BAR was rendered useless by being frozen up. In spite of the tremendous odds against it, the Company showed an amazing record for the day- seven pillboxes, one troop shelter, an old factory, and approximately 150 prisoners."

It was an eerie sight--pitch darkness, men in white advancing toward the enemy, lit up by light from the flame throwers. I try to imagine the feeling from the enemy's point of view!

It was during this action that I lost my runner partner, Burt Klapper. He and I and the Company Commander, Lieutenant Bowman and a medic were together huddled behind a part of a brick wall, receiving incoming artillery. We observed a group of men three or four hundred yards to the side of us, coming back to the rear. The Lieutenant directed Klapper and me to run over and find out if they were our men. We started out running, I in the lead, Klapper right behind. We were obviously targeted by an enemy artillery observer, because an eighty-eight shell came in and exploded about ten or fifteen yards in front of us. When a shell comes in you generally hear the whistle if it is going to miss you, but if it is targeted right on you, at most you have a split second to hit the ground. Apparently my reflexes were a bit quicker that Klapper's. I hit the ground in time; the shrapnel passed over me and hit Klapper in the head and leg. I knew he was badly hit, probably dead. I ran back to where the medic was and told him about it, then Bowman told me to complete the mission, which I did. Later I noticed I had crossed a minefield, the snow hiding the "Achtung Minen" signs. I did not know if Klapper had survived until after the war. The last I saw was a medic team going after him with a sled. After the war I found out he had survived his wounds. That night as we took shelter in a cold cramped part of an old factory, we heard a tremendous explosion. Some of our men had placed an explosive charge in one of the pillboxes, unaware that a huge store of German munitions were stored there. Large chunks of concrete were hurled up to half a mile, luckily none of us were hit. That first day we lost six wounded, luckily none killed.

Somewhere along the way, I acquired a nickname. There was a cartoon character who appeared in the army newspaper, Stars and Stripes. His name was "Sad Sack". He was a typically bedraggled, tired, dirty, down-in-the-mouth, unshaven infantry soldier. One day a buddy remarked that I looked just like Sad Sack. The name stuck, and from then on, I was "Sack". It was easier to remember and say than "Fagerland".

Somewhere along the way, I acquired a nickname. There was a cartoon character who appeared in the army newspaper, Stars and Stripes. His name was "Sad Sack". He was a typically bedraggled, tired, dirty, down-in-the-mouth, unshaven infantry soldier. One day a buddy remarked that I looked just like Sad Sack. The name stuck, and from then on, I was "Sack". It was easier to remember and say than "Fagerland".

I had lost contact with my runner partner Klapper, after he was wounded, but I saw him briefly after the war was over, then never again. Then in year 2000 I learned where he lived and wrote him a letter. Unfortunately, he had passed away a year earlier, but his son replied and we have corresponded. He had written his memoirs too about the war and his time spent in hospitals. He remembered the incident of his being wounded somewhat differently than I did, and he credited me with saving his life. I did not see it that way. His description of me was, quote, "Sack was a gutsy guy and a good combat companion".

I can't rely on my memory for the dates and places we covered during the war, luckily I have a copy of the official Company F Combat Diary to fall back on. At this point in time the day to day details aren't important. As we advanced town by town through the fortifications of the mighty Siegfried Line and in the Hurtgen Forest, we were not only fighting the Germans but also the cold, snow and later the mud. As the casualties kept piling up, more replacements kept coming in to take their places. The Germans had the advantage of having built-in fortifications and every target was previously zero' d in for their artillery. Every crossroad was a death trap for us. At this time I really did not expect to survive the war unless I could get a "million-dollar wound" and get back. According to the official count, our company that started out with approximately 115 men had 54 killed and 163 wounded for a casualty rate of 190%. Why did I come through without a scratch? I don't know. I prayed a lot, but so did everyone else. It seems we were always dog-tired. At the worst when exhausted, cold and numb from sleeplessness I was no longer scared and didn't really care if I got hit or not. I remember one occasion when some of us were walking single file and a sniper was shooting at us from some distance. The bullets were missing us but ricocheting off some burned out tanks by the road. We didn't duck or take cover, just kept walking. One shot passed between me and the guy in front of me.

Occasionally we got a break when in reserve, had a chance to rest, and clean up a bit. Then it was hard to go back into action again. Sometimes the Chaplains would gather us into groups, one Protestant, one Catholic and one Jewish, for a prayer before going back. Then I was scared, as everyone was, wondering which of us would not make it today.

After my runner partner, Klapper was wounded, he was not replaced for quite some time and I was alone in my duties as runner. Normally there would be two so that if one did not make it through, the other might. In the confusion of combat, we did not always know where the "front" was. On more than one occasion, I was sent on a run not knowing exactly where I was. One incident that comes to mind, I was sent from Message Center to find our company CP. This was in the Hurtgen Forest, thick pine woods where every tree was shattered by artillery fire. It was pitch dark and I was not sure where I was. Then I heard "click"-"click", the unmistakable sound of snapping the trigger safety off on rifles. I froze, hardly daring to breath. I knew there were at least two rifles pointed at me, safeties off and nervous fingers on the triggers. There was absolute silence. Were they ours, or were they German? Then I heard a low voice; "password". Thankfully, I did not forget it! I gave the password and asked for countersign, which he gave. Then he questioned me and gave me directions to where I wanted to go.

And so it went. Numerous artillery barrages, theirs and ours. We used to think artillery commanders would not waste an expensive shell on just one person. Not so, I found out. Once when I was crossing an open area maybe three or four hundred yards across, a German observer spotted me and directed 88 mm artillery on me. I would hit the dirt, get up and run, hit the dirt, get up and run. Near misses, but I made them waste at least half a dozen shells. Was it luck, or was someone watching over me?

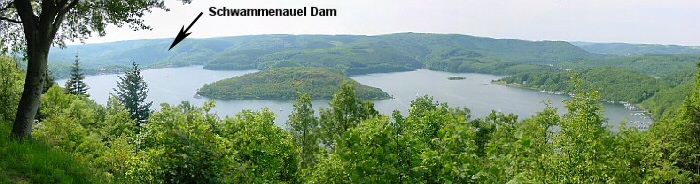

The battles of the Hurtgen Forest in the Ardennes were the fiercest and deadliest of any actions we had. We had to take all those small towns on the way to our mission, to capture the Schwammenauel dam. The towns were mainly deserted and demolished, first by our artillery, and then again by theirs after we occupied them. We hardly ever saw a civilian; they either fled to locations farther east, or moved in with relatives or friends on the farms. The town of Kesternich, for example, was partly taken by our forces, then we were driven back, than we took it again. The Germans deliberately demolished the church steeple so we could not use it for an observation tower. (To jump ahead about fifty years here, when my son Steve, grandson Scot and I along with a group of fellow 78th veterans visited Kesternich, we were greeted and celebrated along with our German counterparts from the German 272nd Volksgrenadiers. We had joint ceremonies and a joint church service.)

The battles of the Hurtgen Forest in the Ardennes were the fiercest and deadliest of any actions we had. We had to take all those small towns on the way to our mission, to capture the Schwammenauel dam. The towns were mainly deserted and demolished, first by our artillery, and then again by theirs after we occupied them. We hardly ever saw a civilian; they either fled to locations farther east, or moved in with relatives or friends on the farms. The town of Kesternich, for example, was partly taken by our forces, then we were driven back, than we took it again. The Germans deliberately demolished the church steeple so we could not use it for an observation tower. (To jump ahead about fifty years here, when my son Steve, grandson Scot and I along with a group of fellow 78th veterans visited Kesternich, we were greeted and celebrated along with our German counterparts from the German 272nd Volksgrenadiers. We had joint ceremonies and a joint church service.)

I suppose every combat veteran carries some memories or visions that we just cannot shed. One of mine is the truckloads of frozen bodies, American and German, that were being shipped to the rear. They were picked off the battlefields, frozen solid into whatever shape they died in, and piled into trucks. It reminded me of my teen years when we shot rabbits for their furs, and buyers would make rounds with trucks to pick them up. They were frozen into all shapes and tossed in. Another time as we were approaching the city of Schmidt, there were bodies along the road that had been run over by our tanks. We couldn't tell if they were American or German, they were so splattered in mud.

Incidents like these, and many others, I have never spoken to anyone about, as it is too difficult. We see interviews on TV where an old soldier tries to talk about the war and gets all choked up. We can talk about the war with fellow veterans, but for whatever reason we cannot talk with anyone else about it. No one but a combat veteran can really understand our feelings about it.

There are probably personal questions that some readers might like answered but are afraid to ask:

Q. What did you have to eat and drink?

A. When we were in a somewhat stable situation, the kitchen crew made every effort to bring up a hot meal once a day. Otherwise, it was "K" rations. Cracker-Jack-sized boxes that we carried with us. They contained either a small can of meat, dehydrated eggs, or concentrated fruit. Also a "dog biscuit", a concentrated dry bar. Each box also contained a small roll of brown toilet paper and a pack of four brown cigarettes. We used bayonets to open the carton, and my eating utensil was a tablespoon, which I carried in my pocket. We carried canteens for water, which we filled at the kitchen truck.

Q. How often did you get a bath?

A. Very rarely! Once in a while we got a break while on reserve, and we had a chance to shave and clean up. Otherwise a little water in the steel helmet made do.

Q. How did you go to the bathroom?

A. The same as any other animal in the wild. Wherever and whenever the need arose. Like other animals, as far from our nest and eating place as possible!

Q. Did you hate the Germans?

A. Yes and no. I certainly hated them when they were trying to kill me and we were trying to kill them; but seeing the pathetic prisoners we were taking, who hated the war as we did, it was hard to hate them.

Q. How many Germans did you kill?

A. That is a stupid question to ask of any soldier, and is not worthy of an answer.

While I was in the Infantry in Europe, Orville was in the Field Artillery in the jungles of the South Pacific, and Kenny was in the Army Air Corps in England. They never spoke much about the war, but I am sure they had some very. bad times too, only different. But our parents must have had it worse than any of us, worrying about three kids, in three different parts of the world, not knowing what is happening to them day by day. If there were any heroes of the war, they certainly qualify for medals.

Speaking of medals, I had lost most of mine over the years, so with the assistance of Congressman Thune, I had all of them replaced. They are the Combat Infantry Badge, Bronze Star, Ardennes/Rhineland Central Europe Campaign medal with three battle stars, WW2 medal, American Campaign medal, Army of Occupation Germany medal, Good Conduct medal, and Expert Rifle/Expert Carbine medals.

The city of Schmidt, overlooking the dam, had to be the most demolished city of the campaign. Historians say Aachen was the worst, and I had seen Aachen, but Schmidt was much worse. It was absolutely reduced to rubble. I remember after the battle for Schmidt, we had a rest, it was a sunny day, and I sat down with my back against what was left of a wall and wrote a letter to Esther. Funny the things we remember! (Again jumping ahead fifty some years, when we revisited the beautiful little city of Schmidt, we were entertained by a group called the "Schmidt Singers." The city we destroyed had come back to life, and the grandchildren of the former tenants were entertaining us!) After taking Schmidt, which overlooked the dam, it was not long before we had the dam in our possession. Mission accomplished! Earlier in the action, our bombers had tried to destroy the dam. Then the priority for the U.S. was to capture it intact, and the Germans tried to destroy it. It came through battered but intact.

Schwammenauel Reservoir

It is estimated that the campaign through the Ardennes and Hurtgen Forest, in the mission to capture the dam, cost about 25,000 American lives. Historians are still arguing whether it was necessary, as it could probably have been bypassed with much less loss of lives. The generals had hard decisions to make, and they were not always the best decisions. Anyway, that phase of the war was over, but we had much more of the same ahead of us. After Schmidt, we started advancing a bit faster. We took town after town on our drive toward the Rhine River. Some were heavily defended, some not. The weather was warming, and mud replaced the snow and ice of midwinter. I don't know which was worse. Walking with heavy boots loaded down with pounds of mud is no picnic either.

March 5, 1944. We were in a battle to take the town of Kuchenheim, and ran into a lot of resistance. This is the day we lost our beloved Company Commander, Lieutenant Bowman, shot in the head by a German sniper. We were all shocked and saddened, as he was greatly respected by us all. He was not one to stay back and let others do the fighting. He was leading the attack when he was killed. Ironically, his promotion to Captain came through the same day.

Grave of Capt. James K. Bowman

310th Infantry, 78th Division

K.I.A. March 5, 1945

Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery and Memorial

Plot D, Row 3, Gr. 31

To quote from the F Company Combat Diary:

"The men were shocked beyond expression. Lt. Bowman had personally led his men through many days of battle; his brave, courageous leadership had been an inspiration to us all. We knew him as a friend of everyone. He had had no favorites and he asked no quarter. His determined leadership had been awarded - his Captainship had come through this day. Many years before, Walt Whitman, shocked by the great Lincoln's tragic death, wrote the stirring poem, beginning, 'Oh Captain, my Captain' in his honor. We too had lost our Captain, a great man."

Fifty five years later, along with son Steve and grandson Scot, I paid my respects to Captain Bowman at his grave in the Henri Chappelle American Cemetery in Belgium. I had the honor of laying the wreath at the ceremonies that day.

Lt. Jones was informed that he was the new Company Commander . He was just my age, twenty-two at the time, but he had shown great leadership in many battles. He was well liked and respected by all the men. A great responsibility for one so young, but he led us well in the battles ahead.

The mighty Rhine River was the next obstacle to contend with. Our leaders had expected the enemy to try to keep us from crossing the Rhine at all costs. Everyone knew that if we got across the Rhine, it would be the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany. So all along the front our forces were advancing toward the river. We knew the Germans were destroying all the bridges, so we anticipated building up our forces at the river and eventually storming our way across in boats. It would be extremely difficult and heavy casualties would be expected. We were at the time attached to the 9th Armored Division. Then we heard rumors that the 9th had captured a bridge intact at the town of Remagen. It was the Ludendorf railroad bridge, and the Germans had tried but failed to destroy it. The 9th had grabbed it and were calling for infantry to cross and hold it. We were it!

There were numerous books written about the capture of the bridge, and a major movie called The "Bridge at Remagen". Our capture of the bridge and the subsequent bridgehead into the heart of Nazi Germany very likely shortened the duration of the war by weeks or even months. This is my recollection of what took place:

We were some miles from the Rhine when we got word that a bridge had been taken intact. After walking for miles on a road where every step was an effort from the heavy mud that clung to our boots, we were utterly exhausted. We came to an abandoned warehouse and went in for a rest. Thinking we would spend the night there, we fell on the floor and loosened our boots. After maybe a half hour, we were roused and ordered to press on. We had to get to the bridge! It was a pitch dark night, so dark you could not see the person in front of you. When we finally arrived at the bridge, we could only see glimpses of it from the flashes of artillery that was falling on it. We crossed single file, by each man holding on to the pack of the man in front of us. Even as we were crossing, the Germans were trying to detonate explosives under it. In our favor, they had underestimated the strength of the old structure, fully believing it would be destroyed before we reached it, so it was not as heavily defended as it could have been. (It was a German foul-up, and two of their officers who were in charge were executed for allowing it to happen.) There were many casualties among our forces, and one man fell through a hole into the Rhine. As soon as we got across, some companies went to the left along the river, and we went to the right. We followed a road by the river for a short distance, then up hill around a bend, out of sight of the bridge. I can say that I crossed the most famous bridge in the world at the time, and I never did see it! In the next couple of days we got a lot of men and material across, while our engineers were frantically trying to build a pontoon bridge. They succeeded and had a flow of forces coming across on the third day, a masterpiece of engineering! On the tenth day after crossing it, the mighty Ludendorff bridge collapsed into the Rhine, taking with it twenty-six American engineers who were trying to repair it. All that remains of the Ludendorff are the two structures at both sides of the river, now turned into a museum. We attended a ceremony there in 2000, along with German dignitaries, celebrating the 55th anniversary of the end of the war in Europe, May 8, 1945.

There is no need to go into details of the next two months of conflict. After the Rhine crossing, there was no way in the world the Nazis could win. We were starting to be hopeful they would surrender and we would survive and go home. However, they fought all the way.

After advancing far into Germany, a large part of industrial Germany, the Ruhr Valley , was partially surrounded. It was our mission to clear out the "Ruhr Pocket". Heavily defended by the large remaining forces of the German army, it would not be easy.

In hindsight, we wonder if this strategy was a major error. The political leaders of the Allies had agreed that we would go only as far as the Elbe River on the outskirts of Berlin, and let the Russians take Berlin. We could easily have bypassed the Ruhr and taken Berlin, saving thousands of lives, and saved what was left of Berlin from the looting, plunder and rape by the Russians. But I guess that was their payback for the tremendous losses they had suffered at the hands of the Nazis.

We were taking prisoners by the thousands, the Russians were advancing from the east, and all their cities were in ruins. How could they win? The Nazis were telling the people they were working on a "secret weapon", (atomic bomb), which would turn the tide.

Toward the last, when we entered a town, every house was flying a white flag. The prisoners we were taking were mostly old men and boys. The young men in the German armies were either dead, prisoners of war, or were fighting the Russians on the Eastern Front.

On one occasion that we joke about, our kitchen crew was trying to catch up and they took a wrong turn. They drove into a town that had not yet been captured, and they were met by the Burgermeister (mayor), standing in the middle of the street waving a white flag. The only time in the history of the war that a city had been captured by a chow truck!

The last action we encountered was the day we marched into Wuppertal, a large industrial city in ruins. There was little resistance, and for us, the fighting was over! We were taken out of action and trucked inland for occupation duty.

Occupation duty; a completely new phase of our lives. The war was not over, as the war in the Pacific raged on, but we had a chance at last to wear clean clothes, sleep in real beds, and eat regular meals. We had to start acting like real people again! After five and a half months of combat conditions, the change in lifestyle was almost overwhelming!

The town of Arolsen was where they stationed us temporarily. It was here that I got a three-day pass to Paris, and I was there on VE Day, May 8, when the war ended. What a celebration! Paris on VE Day! Later we moved to the small town of Dörnberg, near Kassel, where we lived for some time.

When the war ended, the official policy was "non-fraternization" with the German people. Turn thousands of GIs lose in a country with thousands of young women, and we were not allowed to "fraternize"? Get real! That policy went by the wayside very quickly!

Dörnberg was a typical small cowtown. The farmers, all women, (because the men were practically all gone), worked the fields, with cows pulling wagons and machinery. The cows were brought in at night to be milked. As was common at the time, the lower level of the house was the barn, and the people lived above. As there was no manpower, there was probably two or three years accumulation of manure piled in the streets. The flies were horrendous! The sewer system consisted of the wastes from the upper level dropping into waste tanks for the cows below. Occasionally the tanks, "honey wagons" we called them, were hauled out to the fields, (by the cows), and dumped. An efficient system, nothing wasted! The first thing we did in Dornberg was make them haul out the manure and clean up the streets. We also made them put window screens an all the houses we occupied. Dörnberg was a relaxed, although boring place to unwind from the war.

To give us something to do, the army set up classes where we could study various courses. I chose to study the German language, which I never did learn. In the meantime, lest we forget we were in the army, we took training in South Pacific type warfare. We were scheduled to go help finish off Japan. In fact, some units were already on the way. Then the two Atomic Bombs fell!

There are those in this country who say we should not have used the bombs, that Japan was ready to give up anyway, that we slaughtered 50,000 Japanese civilians unnecessarily. Hogwash! Our politically-correct historians, and certainly the Japanese historians, won't admit that they saved hundreds of thousands of lives, American and Japanese! A group of historians recently searched military archives and found detail by detail information on exactly how the invasion of Japan was to take place. Japan was far from ready to surrender! They were training suicide "Kamikazi" bomber pilots by the thousands, which were raising havoc with our fleet. All the men and boys in the country were issued weapons, and fortifications were dug in everywhere. Our plans were laid out in detail, by date, and which units were to be involved. Several divisions were to be sent from Europe to take part. They were prepared to take a million casualties, and many more Japanese would be killed. All the Jap cities would have been bombed and destroyed. Dropping the two bombs saved thousands of lives! We hated the Japs. We hated them for the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. We hated them for their cruelty and inhumane treatment of their prisoners of war. I have a hard time not hating them for never acknowledging any guilt for the war. Their history books hardly mention the war, and never admit any blame.

We were in Dörnberg perhaps two or three months when we got notice we would be sent to Berlin for occupation duty. We were to relieve the 82nd Airborne Division, who occupied the American Sector after it was divided into four sectors, American, British, French and Russian. The Russians were starting to act hard-to-get-along-with already; in fact, we had a confrontation with them on the way to our sector. We had to cross part of Germany that was occupied by them to get to our sector, and they were not going to let us through.

It is hard to imagine the devastation that was Berlin, after months of bombing by American and British bombers, and after the final assault by the Russian army, there was hardly anything left of any value. The Russians had looted everything that could be removed and shipped to Russia, including plumbing fixtures, household items and furniture. Not to mention valuables like art and museum items. It was said that a large percentage of the women had been assaulted. We would see starving people scrounging in garbage cans for scraps of food.

There was a sort of black market where certain things could be purchased if one had the proper currency. German currency was worthless, and the currency printed by the U.S. Army was not available to them. The best currency, believe it or not, was cigarettes! Americans could buy a limited amount of cigarettes from the PX and one could buy anything with them, so of course a lot of them got into the black market. If one walked down the street smoking a cigarette, he would be followed closely by civilians, and if he flipped the butt, there was a scramble to get it. That was the pitiful situation when we arrived. Eventually enough food got through to prevent starvation, and after the Marshall Plan took effect, convoys of food and supplies started coming in.

There were many incidents between the Americans and Russians. We were not allowed to enter their sector, but they thought they could enter ours at will. To prevent serious clashes, we were not allowed to carry firearms, except when on guard duty, but they always carried their weapons. I and many others carries a small handgun for protection. Some of our guys who had cameras would try to take pictures of the Russians, but they always wanted to be photographed with their rifles pointed at you! Rather uncomfortable, as we were taught in the army to never point a firearm at another person unless you intended to kill him.

Finally I had enough points to be discharged, and was on my way home. We were trucked to Antwerp, Belgium, and put on a ship for the U.S. The ship was a so-called "victory ship", a rather small, cheaply built mass-produced ship that had a history of breaking in two in a storm. And find a storm we did! To me it felt like the hurricane of the century, and every time the bow would come out of the water and crash into the next wave, it felt like it would surely break up! After surviving months of combat, were we going to die on the way home? We were a scared bunch of soldiers!

The storm passed, and in a few days we were pulling into New York Harbor, where we were greeted by our favorite lady, the one holding the torch, guiding us home. I won't try to put into words the emotions we all felt. As we were disembarking, groups of Red Cross girls were handing out donuts and milk. The girls knew what the guys really wanted, but milk was high on the list. We had not had a glass of real milk for many months, and did it ever taste good!

The rest was routine; we were put on a train to Camp McCoy, Wisconsin for processing. Sign this paper; here is your discharge paper and a hundred dollars, and a train ticket to Noonan, North Dakota. A handshake, Good Luck! I was a civilian!

Some afterthoughts, as I look back on the most historical event of the century, World War Two:

From the attack on Pearl Harbor forward, it was Total War. Every man, woman and child was at war. Sixteen million men and women served in the armed forces. On the home front, women went to work in the factories and volunteered for all kinds of services. Old people raised "Victory Gardens". Children collected every imaginable thing for recycling, from aluminum foil from cigarette packs to zinc from toothpaste tubes. Hundreds of items were rationed, from gasoline and tires, to shoes and nylons, sugar, and coffee.

When we entered the armed services, it was not for a specific period, it was "for the duration and six months". We were guessing it would probably be five years. We were always sure we would win, but it looked bleak for a time.

In 1942, the Japs had captured the Philippines, Guam, all of what is now Indonesia, Korea, much of China, all of the South Sea Islands, the Southeast Asia countries, and were threatening Australia. They had destroyed most of our fleet at Pearl Harbor.

In Europe, Hitler had overrun all of Europe, including Norway and the Balkan countries, and was almost at the gates of Moscow. The Germans and their ally, Italy, controlled all of North Africa. German bombers were pounding Britain. Our merchant fleet, trying to supply Britain was being sunk mercilessly by German submarines.

In my opinion, two situations can be credited for saving the Allies from total disaster: One was the Royal Air Force managing to hold off an invasion of Britain, and the other was a blunder by Hitler, his invasion of Russia. He failed to get a quick victory there, and got bogged down in the Russian winter.

Again, in my opinion, there was a turning point, quite early in the war, when Germany's loss was inevitable: when American and British forces drove the Germans and Italians out of all of North Africa and got a foothold in southern Europe, and when the Germans were driven back by the Russians at Stalingrad. From that point on, the German generals knew they could not win. A group of generals did plot to kill Hitler, but it failed, and of course, they were all executed.

In the Pacific, Americans were taking back island by island, with terrible casualties, but they were winning the war. At Iwo lima, eight thousand Marines died, to capture a one-square-mile island.

Looking at today's war in Iraq, in comparison, while it is tragic to lose any lives, but any war will cost lives. The headlines every day speak of two or three more lives lost. In WW2, in the approximately 3 1/2 years of war, we lost about 450,000 killed. That averages to about 352 men killed every day for the entire period. Hardly a comparison. Today, no one is sacrificing except the men and women who are actually fighting, and their families. Everything is plentiful, we can have anything we want. No comparison there either. To get back to civilian life, a brief outline of my deeds and misdeeds during that period after the war. No one to tell us what to do. We were on our own. It was a different kind of life. We could do anything we darned pleased. We were free!

~~~ Warren L. Fagerland ~~~

Feb 19, 1923 - † December 20, 2019

Thanks Warren for your kind permission to allow me to re-post your wartime story.

Source: http://www.dakotastories.org/homefront/independent/images/warren%20fagerland%20.pdf