78th Infantry Division, 309th Infantry Regiment, L Company

So many years have passed, but it seems like yesterday.

I have relived the experience countless times.

World War II was raging. The Battle of the Bulge was finally over, and we were now pressing more deeply onto Enemy territory.

As an infantry replacement, I had been assigned as partner to a young soldier who carried a B.A.R. (Browning Automatic Rifle).

I was to help carry some of his ammunition together with my M.I. (Military Issue) rifle and gear.

Browning Automatic Rifle

My partner and I soon became close friends. He being from the East and I from the upper Midwest, our backgrounds, faith, and nationality (he was Jewish) were entirely different. But those things were soon forgotten in the close relationship formed during front-line combat. We lived, ate, and fought together; we were never separated for any length of time.

Will never forget the Siegfried Line with its dragon teeth and heavily fortified concrete pillboxes guarding it. Although it was a formidable obstacle, we were able to break through. A few enemy soldiers were losing heart, but the war was far from over. Many battles were yet to be fought with thousands of casualties before final victory could be won.

Our 78th Infantry Division was given the assignment to capture Schwammenauel Dam. An important objective, it controlled a large area that would be devastated by floods should the enemy demolish it. The valleys below would be flooded and further progress would be difficult. We moved toward the objective and found ourselves early one morning on a wooded hillside.

Schwammenauel Dam

Wherever we paused, our first assignment was to dig a foxhole. We needed protection. Yet even in foxholes, protection was limited. Artillery or mortar shells hitting the branches of trees nearby would scatter shrapnel everywhere, striking those even in the deepest hole.

This particular morning a strange quietness prevailed as dawn broke. My partner and I started digging the foxhole we would share. The going was slow because the ground was hard and rocky. We began taking turns digging until I was weary, and the hole was only about 2 ½ feet deep.

My partner approached me and said, “I’ll take your place for awhile.” Sitting at the edge of the hole, I had been using my shovel as a pick to break through the hard ground. Without hesitation, I willingly changed places. He sat down in the exact position where I had been and began to dig.

I turned and walked up the hillside about 50 feet when, suddenly without any warning, an exploding shell shattered the stillness. After a few minutes, all was quite again. I called to my friend who still sat with his shovel held fast in his hands. There was no response, so I hurried to his side. He was dead! He had been killed instantly by a large piece of shrapnel piercing his steel helmet.

Suddenly I realized he had taken my place. His life was gone; mine had been miraculously spared. I will never forget my friend. He died for me.

Although the sights and sounds have long since faded, the experience is indelibly imprinted on my mind. As a combat infantryman, I had come close to death many times during World War II, but no experience compared to this on night of terror.

As part of the 78th Infantry (Lightning) Division, we soldiers were assigned to a place in the heart of Germany and were pressing forward rapidly. Late in the evening, we thought we had arrived at our stopping place for the night at the base of a hill. For protection, we began to dig a foxhole.

Usually, two men were paired off as a team, but since my partner had been killed earlier that day, two other soldiers and I became a party of three. Bill was a gentle, likable fellow from Oklahoma. The other man was well known for his carousing and cursing, but he was quite adept with a shovel.

No sooner had we dug our foxhole and made preparations to settle in for the night when we were given orders to move to the top of the hill about 100 yards away.

At the top, we immediately removed our gear and started to dig another foxhole. The ground was rocky and hard. We had dug about two feet when, without warning, intense artillery fire set in. Our only recourse for safety was our shallow hole. We piled in, wedged together, with our faces to the ground.

Shells fell closer. Words cannot describe the sensation of hearing a shell fired then the screaming sound intensifying as it nears its target, and finally the deafening explosion with shell fragments flying everywhere.

We could do nothing but lie there and wait, listen and shudder. The shelling lasted about 10-15 minutes with one round after another in rapid secessions.

Even with our eyes closed and our faces pressed into the ground, we could see flashes of light as exploding shells came near. It was a miracle that none of the tree bursts struck us.

During that time, there was one thing no one had to tell us to do. We prayed earnestly.

Finally the shelling stopped. We decided to go back to the hole we dug at the foot of the hill. While collecting our gear, Bill found that shrapnel had shattered the stock of his rifle. My canteen had been pierced and water ran out when I picked it up. Our rifled and canteens had been lying at the edge of the hole!

Almost immediately after we settled back in the larger foxhole, the shelling began again. However, we felt much more secure this time.

Early the next morning, we began moving forward again. When we walked past the shallow hole where we had huddled the night before, we were shocked by what we saw! An enemy shell had made a direct hit in that very spot. Had we not exited when we did, none of us would have survived. God again had spared us form the certain death in answer to prayer.

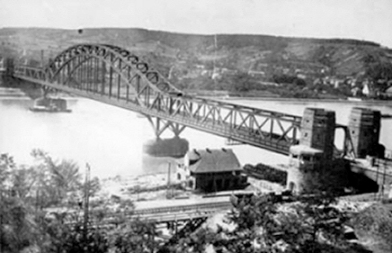

For eight days thousands of American troops moved crossed the Rhine River in Germany over the Ludendorff Bridge. It was March 1945. The Ludendorff was the only bridge remaining, the only one the Germans during World War II had not blown that up in their vain attempt to keep our American forces from advancing.

The day after my platoon had crossed the bridge; we were engaged in a battle in which we suffered heavy losses. We walked into an area that was strongly fortified. It was something like an ambush. When the fog suddenly lifted, most of our men were out in the open and quickly cut down by waves of enemy rifle and machine-gun fire. I will never forget seeing the bodies lying side by side after they were carried off the field of battle.

The next day as we pressed further into enemy territory, we were walking single-file through a partially wooded area. Suddenly the young man in front of me turned. His eyes were wide with fear as he said to me, “Let’s get out of here! We’ll never make it through alive.” He was 18, a native of Texas, and ready to turn and run.

I replied, “God has seen us through this far, and He is able to help us the rest of the way.” That word of encouragement was enough to turn him back into the column and help him continue moving forward. More of our men were killed that day, but the Lord was there to help us.

A few days later this same young man was awarded a Bronze Star for bravery in helping to knock out a machine-gun nest.

It was utterly devastating! That day, March 8, 1945, stands out as the most terrifying day by far of anything we had previously experienced. Our L Company, 309th Regiment, part of the 78th Infantry Division, had just crossed the Rhine River in our march across Germany during the final months of W. W. II. Although defeat was imminent, the German army still offered stiff resistance. They tenaciously defended this last natural barrier by blowing up all the bridges. Only one bridge remained intact, the Ludendorff Bridge at the little town of Remagen.

We marched all night to reach the bridge, which had been captured the day before in a brilliant swift move. The 78th Division was then called to take advantage of this unexpected achievement. I remember the dramatic sight in early morning looking down from the hills just above Remagen and seeing the bridge below. Through the heavy overcast a German dive-bomber broke through the clouds, dropping its bomb in a vain attempt to demolish the bridge. We watched as the bomb overshot its mark, falling harmlessly into the river.

The Ludendorff Bridge had been built years before as a railroad bridge. Upon capturing it American soldiers placed heavy planks across the rails to facilitate crossing by infantry, tanks, trucks, and jeeps. We got to the bridge, pausing momentarily, waiting for a lull in shells hitting the superstructure. We then dashed across, and soon occupied the little village of Erpel on the far side.

After returning from a brief night patrol, sleep came fitfully, with artillery shells continually rocking the house we occupied. Early next morning we moved forward, intent on taking a hill from which another unit had been driven back the day before. Heavy fog lay over the landscape obscuring our vision. We captured a few German soldiers who warned of strong resistance ahead. Upon reaching the top of the hill, orders were given to spread out and dig in. My squad leader, Sgt. Luther Raine, just ahead and to my right, signaled me to join him in a shell hole, which offered some protection and also made digging far easier. The other men in our platoon hurriedly moved out and across the open area to our left, little realizing what awaited them.

My squad leader and I removed our backpacks and started digging, when suddenly the fog lifted. At that same moment rifle and machine gun fire began sweeping the hillside. Our men in the open had no chance of escape. I ducked low in the shell hole and began firing back, when suddenly a bullet careened off my steel helmet making a crease on the right side. An inch or two further toward center would have finished me off. I had witnessed previously that shrapnel or bullets could quite easily penetrate steel helmets.

Almost as quickly as it had lifted the fog again settled down. Gunfire stopped. All was quite except for agonizing cries of strong men in the throes of death. It is a sound that will always remain vividly in memory. No wonder war has been likened to hell. After a few minuets my squad leader, badly shaken by it all, said “Let’s get out of here; we’ll never survive otherwise.” With that, he leaped for a hedgerow nearby. I followed close after him. We had gone but a few steps when a mortar shell burst directly in front, knocking us to the ground. Picking myself up it felt as if I had been hit over my entire body. I was certain “this was it,” but soon discovered my wounds were superficial, with nothing but a trickle of blood running down my face.

My squad leader lay completely still, except for heavy breathing. His steel helmet lay on the ground beside him. He was bleeding profusely from a huge gaping wound that had removed a portion of his skull. Totally, unconscious he continued breathing heavily. Although I knew nothing could save him I removed his first-aid bandage and placed it over the flowing wound. I watched as strength left his body and as he soon breathed his last. I looked at my hands; they were covered with blood. A strong man lay dead. I’ve often thought of his wife and little children back in Louisiana who would never have the joy of welcoming him home.

Somewhat in a daze I wandered back to the area we had so recently left. One of our tanks rolled up and a tank observer came to meet me on foot. He inquired as to where the enemy was entrenched. After pointing the tank gunner who lobbed two or three shells into the area. Moments later a stream of 70 to 80 German soldiers in long overcoats hands upraised and placed behind their heads, came streaming out of the wooded area.

The battle was over, but at a heavy cost of precious lives. Almost half our platoon lay dead on the field. Later that day their bodies were carried off and laid side by side, almost reminding me of cordwood. But these were human beings, my close friends whom I had come to know and love. During the next few days we tried to regroup and continued on. The war wasn’t over yet and there would be more battles to fight, more lives that would be lost, but nothing quite compared to that day.

~~~ Peter J. Dahlberg ~~~

In remembrance of Peter J Dahlberg.

Rev. Peter J. Dahlberg, 87, Rapid City, passed away on January 9, 2013.