Company Commander of

Co. 'E', 39th Infantry Regiment,

9th Infantry Division

Excerpted from "The Tale of a Civilian Soldier" by Kenneth Hill

LAMMERSDORF

We arrived at some railway station in Belgium and loaded on trucks to the 9th Division headquarters where we were dispersed to our respective regiments and battalions. As is the case with all the replacement depots, the group was made up of returning wounded as well as fresh replacements for those that were too badly wounded to return to action and for those that were killed. I arrived at Company E headquarters on September 12 in Verviers, Belgium, the day after our battalion had liberated that town. Captain Gordon was still the company commander. He had been wounded and returned before me. He was the only officer that was with Company E when we landed in Normandy. Every man in my old platoon had been killed or wounded, with some of the wounded returned to fight again. It was almost like joining a company that I had never seen before. Almost the only familiar faces were those in rear echelon jobs, such as supply men, cooks, drivers and clerks and a few rifle platoon men that had made it through or had been wounded and returned.

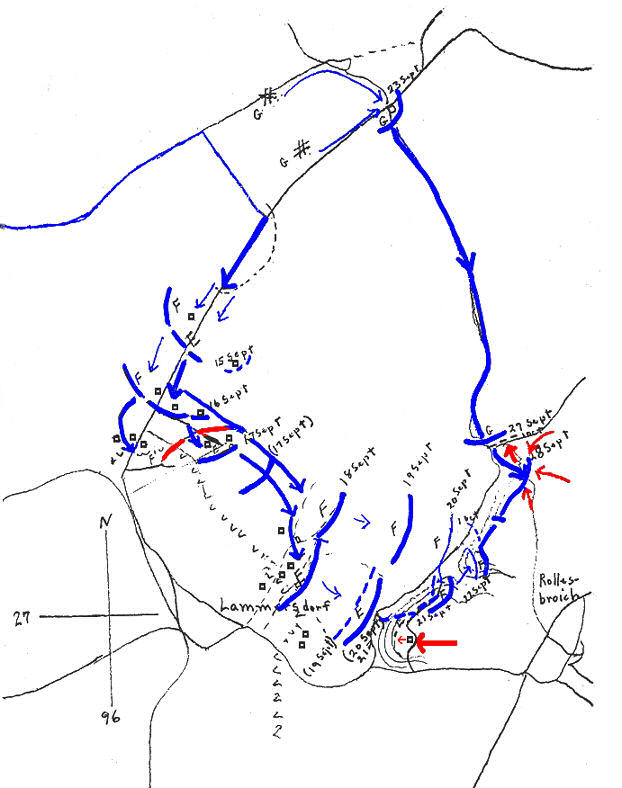

On September 13, we headed out toward Germany on foot. I had the first platoon. Later on we loaded on T.D.s (Tank Destroyers) and crossed the German frontier at 11:00 AM. We reached Reinartzhof without resistance and set up defense for the night. No chow reached us that night.

The following day we advanced about two and one-half miles before we were fed a hot lunch. We went into battalion reserve positions for the night. The next day we advanced on foot for two miles starting at about 11:00 AM. We then loaded on tanks and rode five miles and hit resistance. We unloaded from the tanks and went into the attack and inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy. We captured an A P gun and a pillbox. We had three GIs and an officer killed. This was one mile west of Lammersdorf, on the south edge of the Huertgen Forest.

Daniel Boudin (we called him Jack), the French boy who joined us before Cherbourg, was back with the company after having been wounded and rejoined the company near Verviers. On this action, the platoon that he was with was in the lead while my platoon was in company reserve. They got out about 200 yards to our front and were pinned down by machine gun and mortar fire. I was looking around the corner of a brick house trying to assess their situation so we could plan a flanking attack with my reserve platoon. A burst of MG fire came at me and chips of brick spattered my face. Meantime, the lead platoon pulled back to where we were but about six or seven of the men didn't make it back with them. Jack was one of them. We went ahead and made our flanking attack and gained the position just at dusk. As we arrived at the objective, Jack showed up with three or four of the other guys. They had been pinned down so close to the German positions that they hadn't dared pull back for fear of being hit. Jack was wounded his second time a few days later when Captain Gordon was wounded. I never heard anything further of him until I had been home almost a year when I received a letter from him, written in French. I learned of a young lady that lived down the street about two blocks from Mom who was French and could speak English. I had her translate the letter for me. The letter and the translation is among my memoirs. In the letter he was asking my help to receive the American Purple Heart medals. I wrote a letter supporting his application and told all I could remember about the action. I hope he got them.

The next day, the 16th, we started the attack again. My platoon advanced about 200 yards before hitting resistance. A platoon of tanks (4) came forward to support us and we advanced another 500 yards. We had seven GIs and one officer wounded.

The next day, the 17th, we attacked a series of pillboxes, or bunkers. We captured four of them along with 50 prisoners. We had one wounded and one killed. I had one squad leader that captured three pillboxes with his squad. He was our mail clerk when I first joined the company and when we were in England. His name was Frank Gabbert. While I was in the hospital he had been promoted to sergeant and made a squad leader. He was really a clean cut kid, a nice guy that everyone liked. He was a great favorite of Captain Gordon.

These pillboxes were a part of the Siegfried line. All had at least one large room and some had two or three. The concrete was at least four feet thick, and the doors were thick steel. There were apertures at the sides with slits to fire their guns through, with the slits in about a one foot by two foot window of about two and one-half inch steel. When we laid artillery and mortar fire along with rifle and MG, the krauts would leave their foxhole positions for the safety of their bunkers, or pillboxes. We would then move in on their blind spots, and have them trapped inside. There was no way to get to them in there but would persuade them to surrender. There will be stories following about some who didn't readily surrender.

It was somewhere along this time that we were attacking a bunker. A machine gun from one of the apertures was giving us trouble. They were well camouflaged but we spotted the aperture this one was firing from, about 150 yards away. One of our Sherman tanks had moved up and I crawled up on its back to point the target out to the tank commander. I was looking and pointing around the right side of the turret at the aperture when it burst fire at us. Bullets hit the side of the turret and I got some lead spatters. So did the tank commander who had his head up out of the turret. Very quickly the tank leveled its 75 mm gun at the aperture and fired one round. This put a 75 mm hole right through the two and one-half inch steel aperture. We had no more trouble from that gun.

On the 18th, we continued the attack. We got momentarily pinned down by machine guns from pretty close by. A flanking maneuver by our reserve platoon relieved us and we proceeded to capture three more bunkers and 19 PWs.

On the 19th, we jumped off to attack a hill situated about one-half mile southeast of Lammersdorf. We started out across the open with four tanks and us crowded in behind and beside the tanks. Mortar fire and shaped charge antitank shells started falling around us, at which point we and the tanks should have charged. Instead, the tanks threw into reverse and started back as fast as a man can run. We stayed and held our ground, taking cover where we could find it. Make no mistake, tanks are not worth a damn without infantry out front. They are fine for exploiting a breakthrough but the infantry makes the breakthrough as they had at Saint-Lô.

We got the tanks, machine guns and artillery to lay fire on the hill we were attacking. It was a steep hill with a long shallow valley leading up to it. Consequently, we were able to get almost to the top of the hill before the supporting fire had to lift. By then we were almost upon the Germans and got the hill before they were able to reorganize after the very effective fire we had laid on them. Captain Gordon and Jack (Frenchie) were amounts our wounded and Lt. Brandenburg took command of the company. We captured 38 prisoners and there were dead Germans lying all around. At the top of the hill there was an open fenced field to the front, with heavy woods and a steep slope to our rear, where we had come from. The corner of the field was just to our right and then woods along the right side of the field and about 150 yards to the right of that to a hard top road. We had taken the ground just to the corner of the field so the woods across the corner from us and along the right side of the field was occupied by the Germans. I was about thirty yards from the corner, standing with our MG section sergeant and one of his squad leaders, pointing out where he should set up a MG when a shot came from the underbrush near the corner, hitting Tex, the section Sergeant square in the chest. He was standing between me and the squad sergeant. As he went backwards, he cried "Mama", we caught him and dragged him into the brush. He was dead by the time we laid him down.

We set up our defense line along the open field to the corner, then downslope to our right rear from the corner of the field. The next day, our objective would be to attack and clear the woods along the right side of the field down to the bottom of the hill to our right front. Just in front of us about thirty yards into the open field was a bunker. We had men posted around it with Germans trapped inside who refused to surrender and come out.

About 10:00 PM that night, the Germans laid heavy fire on us and rolled a tank into the front of the pillbox. The men we had guarding it were scared off when the tank appeared and before we could organize counter measures and get bazookas into position, they had rescued the trapped Germans and fled. Then things quieted down for the night.

The next day, at 9:30, September 20, my platoon and the second attacked down the right side of the field and cleared the hill to the front and to the right to the hard top road. We captured a bunker and 56 PWs. Lt. Brandenburg was wounded and I took command of Company E.

During the night the Germans attacked about 10:00 PM with two tanks and supporting infantry. When we had taken the hill we had zeroed in our artillery to fall on likely avenues of counter attack. As we zeroed in a location we would assign a concentration number. Then if a counter attack came, we could call for artillery barrage by concentration number. As this counter attack came, I called for a concentration number that was 200 yards to our front. When the barrage came, almost the whole barrage fell on our positions, wounding and killing eight GIs. The artillery observer that was with us explained later that a weather front had moved in since we zeroed and we had both a change in wind direction and a heavier atmosphere, causing the shells to fall short. This didn't help matters and the men on the point to our right front fell back to our original positions. Two or three of our retreating GIs fell off about a ten foot embankment in the dark.

The next morning as I toured the company area to assess our position, I came to this embankment. As I and two or three GIs stood there, suddenly there appeared about a dozen Germans below us. We were prepared to open up on them, and my runner did fire a shot before we heard, "Don't shoot, don't shoot, Americaner." Then we realized that the Krauts had their hands on their heads. The GI who had called out was PFC Koonce. My runner had hit him in the hand with his shot. He was one who had not fallen back during the night and had persuaded these Germans to come in with him and surrender. Crazy things do happen in war. The runner that fired the shot was at our last division reunion at Hyannis in 1988.

Later in the day, we organized a counter attack to regain the ground that we had lost during the night. Before we opened up, we had a megaphone and called to the Germans to surrender, that if they didn’t, in 15 minutes we were coming after them. None came so we laid in our mortars and artillery and as soon as that lifted, two platoons headed into them with marching fire. Marching fire is when the attacking unit just starts moving forward, pumping lead into anything that looks like it might hide a man. Each man started with two bandoliers of ammo, one crossed over each shoulder, in addition to his rifle belt full. In ten minutes we had cleared the area, captured 150 prisoners, and had light casualties. One of our platoon leaders was killed, a Lieutenant, with a bullet in the center of his forehead. In following up the attack, my runner, radio man and I captured a half dozen out of their holes that the company had flat over run.

A few minutes after the completion of this counter attack, I was up at the forward point when a machine gun across the road and 300 or 400 yards to our right opened up on us. I hit the dirt and watched dust spurt up about ten yards up the slope from me and one of our men was wounded there. Instead of lying flat, he then got up on hands and knees and started crawling with me yelling for him to get down and lay flat. Another burst came and I could see the bullets hit him in the side. We got the machine gun quieted down with mortar fire. This was another close one for me.

This was the extent of the advance in this area by our regiment, but we held here for another 12 days in defense. From the 18th to the 30th of September, we had 53 casualties, with most of them from the rifle platoons.

On September 22nd, after we had regained the lost ground, Captain Curry arrived to take over the company. Colonel Gunn had asked if I was ready to take the company, or did I want a replacement. I asked for the replacement, with the thought that I would then be executive officer, working more in the rear with logistics, supplies and transportation for the company. I may be dumb but I'm not stupid! Besides, I really didn't want the responsibility. Sure enough, Curry appointed me executive officer.

There were a couple of incidents that occurred during the taking of this hill that I remember vividly, but not the particular day they happened. Once, I believe about the time Tex was shot from between me and the other sergeant, a burp gun opened up down the fence-line at us. As we ran for cover, my runner pitched forward on his face. A bullet had hit his poncho, which was folded and draped over the back of his belt, hitting him in the lower back. It didn't penetrate the poncho but gave him a pretty good bruise on his back.

Another time an artillery barrage came in and a small piece of shrapnel hit PFC Grindean in the back of the neck just at the base of the head. He made it on to cover, but he was staggering. We got him down off the hill to the aid station and thought he was going to be OK. We heard later that he didn't make it.

In this position we had dragged all the German dead to one spot, laying side by side. There was 22 of them and it seemed like they laid there three or four days before the graves registration people came and picked them up. Also we had a GI killed on night patrol about 250 yards to our front. They insisted on carrying him as missing in action, although we could see him laying out there for two or three days. Finally, we had a detail go out there and pick him up one night. Doing that there in the daytime was out of the question.

Off to the right side of our positions we could see across the hard top road to K Company's positions, about 300 yards away. They had a pillbox that was clearly in our view. We watched them all day setting charges against the door and exploding them, trying to make the German occupants surrender. According to our Division History they used artillery, anti-tank rockets (bazookas), smoke, 24 pounds of dynamite, 18 Teller (German) antitank mines, and 400 pounds of TNT before the 38 occupants were forced to surrender. Many of them had broken ear drums and were suffering from shock.

When Captain Curry showed up to replace me, there was also two platoon leader replacements as well as a number of GI replacements. The two shavetails were Lieutenants Shackton and Wells. Ever since we had been here, several times a day we would hear the whishing of large caliber shells (probably from a railway mounted gun) whishing over our heads and landing around Lammersdorf to our rear where battalion headquarters was. I was taking Captain Curry and the two Lieutenants along our lines to show them our defensive installations. As we rounded the fence corner, one of those shells came whishing over our heads. As soon as they heard it the replacement officers hit the dirt. When they did, out of pure reflex I did too. I got up, feeling foolish, as I had been ignoring the things for three days. It was an indication of how nervous these three men would be in days ahead.

We held in these positions for several days, with occasional artillery barrages but no more counter attacks in my area. There was additional attacks against units situated to the left of Company E. We had extended our lines to the left to occupy F Company positions as they were pulled out to battalion reserve. On the 26th, Captain Curry was wounded during an artillery barrage after having seen only four days of action, all in this one defensive position. I again assumed command of the company until Captain Stanford arrived to take over on the 29th.

On October 4, the 4th Cavalry group came in and relieved us, so we could move to the north and attack toward Germeter, Schmidt and the Roer River dams in the Huertgen Forest.

GERMETER: THE HUERTGEN FOREST

After relief by the 4th Cavalry, we marched six and one-half miles to an assembly area where we spent the next day enjoying rest, shaves, haircuts and hot chow. We also got some more replacements here. Captain Stanford decided he needed a 3rd platoon leader worse than he needed an executive officer, so I was assigned that job. Well, the great idea was shot down; back to the front lines for me.

On October 6th we moved about one mile into position as regimental reserve, protecting the regiment’s left flank, then on the 7th we moved forward another 700 yards, met resistance and in the ensuing battle had 11 wounded and one killed. On the 8th we moved another 400 yards, still guarding the regimental left flank. On the 9th we advanced up a high hill under heavy MG and mortar fire and secured positions near a road junction. We had three wounded. Then on the 10th, we followed a heavy artillery barrage, gained some ground, securing the road junction and had two GIs killed. On the 11th, we attacked three-fourths mile under heavy artillery and mortar fire and cut the Germeter to Huertgen road on the northern outskirts of Germeter. We had six GIs and two officers wounded, one of which was Captain Stanford. He was wounded about 300 yards before we reached Germeter, so I had the company the rest of the day - the rest of the war, in fact. I had two platoons across the road about two hundred yards and one on the road facing toward Huertgen. Company F was on my right.

I set up my C.P. in a saw mill about 50 yards off the road. We held in this position until October 20. During this period there was occasional artillery and mortar fire, and we did active patrolling. At one time, one of my platoon sergeants, Sergeant McKenna, came to the C.P. and while there an artillery barrage came into the line positions. When he got back to his foxhole, his sleeping bag was in a tree about 15 feet up. A shell had hit in his hole while he was gone. A couple days later at night, he went to the rear with a detail to pick up rations and ammo for his platoon from our jeep. It started raining and he and another platoon sergeant crawled into a pile of brush across a fire break. This brush was piled there by the Germans before we captured the area and they had mined it. They triggered a mine and both were killed. Pete D'Allesandro was then made platoon sergeant. He later was captured and was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Another night, our kitchen and supply people were bringing rations and ammo up on a halftrack. Our armorer-artificer was riding on a front fender, guiding the driver along the trail in the dark. The halftrack hit a mine and he was killed.

About twenty yards from my C.P. near the trail leading to our lines lay a dead German, near the end of a stack of logs waiting to be milled. He was lying on his back with big blue eyes staring straight up. he was there for about three days before the graves people picked him up. Several times I walked out to the lines and a couple times on the way back I'd be preoccupied with my thoughts elsewhere, looking at the ground but not really watching where I was going. Then I'd be looking right into those eyes and it would startle me so I would jump out of my skin.

On October 15, Lt. Ray P. Firestone joined us as a replacement. It was his birthday and I had some gin. We toasted his birthday, then I showed him to his platoon. He was a fiery red-headed art teacher from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. He became the best friend I had "over there.” He made it all the way through to the Elbe River. During the Remagen Bridgehead battle he was given command of F Company. We left the division together and were together until we headed home. I have a couple of pencil sketches he made of me.

One problem we had during this period was keeping our lines of communication open. Battalion headquarters was so far back in the woods they were hard to reach by radio, especially after the batteries got a little weak. We always laid sound power telephone lines back to battalion when we were in defensive positions. This would give us connection through a switchboard to the other companies. It seems like every day shrapnel from artillery and mortar fire would cut the line. It was the chore of the company runners to go out and trace the line until they found the break. There was always an argument as to which of them did it last and whose time it was now. I was usually amused by that but often had to exert myself and order one or the* other to trace the line. There were areas along the line that were under observation of the Germans, so it was really a serious matter with them as to who got to stay in the meager protection afforded by the C.P.

On October 12, there was a heavy barrage early in the day and we lost communication with battalion. We didn't hear from them all day long. What had happened was that a crack German regiment named after its commander, Colonel Wegelein, the Wegelein Combat Team, had attacked the regiment's left flank. They had broken through behind my positions with G Company in reserve bearing the brunt of the attack. They got all the way to battalion headquarters where the headquarters personnel had to fight as infantry men. They managed to drive them back and regain lost ground the next day. The woods were so thick we couldn't even hear the sounds of battle a half mile behind us. It was late in the day before we realized Germans were behind us. We wheeled a platoon around to face the rear, but we never saw any German troops behind us except their medics. It was about 150 yards to the edge of the woods behind the saw mill and we saw a man carrying a large white flag with a red cross on it. There was about four men with him, I assume ambulatory wounded.

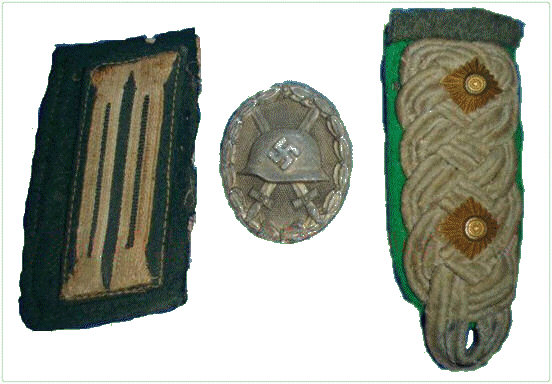

Earlier in the day, one of our platoons saw a German officer and a soldier to their front in the brush about 150 yards. Sergeant Knight, Oklahoma City, leveled his rifle and let him have it. It turned out it was Colonel Wegelein, the commander of the attacking German regiment. I assumed he had gotten lost and separated from his forces and had unluckily stumbled into our defensive line. A lot was made of the incident and the Colonel insisted that I write Sergeant Knight up for a silver star medal, although there was nothing unusually heroic in the action. Colonel Wegelein was a tall man, about 6’4". I got his walking cane and carried it with me to the end of the war, and thus acquired the nickname "STICK". About two months after the war I was sent to Reims hospital for about three weeks. While I was gone the cane disappeared. I also got his insignia of rank from his shoulder epaulettes, and still have them.

The insignia worn by Oberst Wegelein,

commander of the German forces that were fighting against men of the 9th Infantry Division.

Kenneth Hill and his radio man (who shot Oberst Wegelein) took all the insignia's from his uniform, and kept them.

On October 21, we were relieved by K Company and moved to a regimental reserve position. We had one man killed on this day. The next day we moved about one-half mile and relieved I Company in their positions just west of Germeter, protecting the regiment's left flank. We had one man wounded and one missing.

On October 22 to 25, our division was relieved in line by the 28th Division. The company that relieved mine was E Company of the 109th regiment, the company I was in in Florida when I got shipped overseas. They had a different bunch of officers, although they hadn't yet been in combat very long. My old platoon sergeant and another that was there when I was, had received battlefield commissions and were now lieutenants, specifically Vance and Beers. As we were moving out as they were moving in we had no chance to visit, just say "hi" and be on our way.

~~~ Kenneth Hill ~~~

Kenneth Hill

December 1944 in Jüngersdorf

Posted here with kind permission of the son of the former Capt. Kenneth Hill.

Special thanks to Albert Trostorf who provided me Kenneth Hill's "The Tale of a Civilian Soldier" story.