C Company, 1st Bn, 28th Infantry Regiment

8th Infantry Division

HELLFIRE IN THE FOREST

A true story by an American G.I in the Hurtgen Forest Campaign.

When growing up in Brooklyn, N.Y. I often wondered what kind of future I would have. I never, for one moment, thought that I would be involved in a World War. I didn't know that the Government was going to take care of my future by drafting me on April 10, 1941. My training seemed endless because my outfit didn't see combat until July 4, 1944. All that training, which I had thought was useless, proved to be a lifesaver.

We landed on Utah Beach on July 4, 1944 and fought our way through France. When combat in France ended, we were moved to Luxembourg. We were suddenly pulled back from our watch and patrolling near the hills facing the "Siegfried Line". The Weapons Platoon and part of a Rifle Platoon were housed in a town schoolhouse. Late one night, November 17, 1944 there was quite a commotion going on all around us. Part of another outfit was bedding down around us. From them, we could hear moaning, loud cries, shrieking and even crying. This continued throughout the night. When daybreak arrived, we looked around us and saw a bunch of haggard, tired, beaten and depressed soldiers. They had come off of the fighting line after three weeks of attack in the Hurtgen Forest in Germany. We were to be moved out and they were to take over our positions and patrols along the Luxembourg border. This trading of places was done mainly to give the newly arrived troops a much deserved, "Rest Period". We were truly glad to give up the easy life we had to those so badly in need of rest. The battered troops that we relieved were part of our 28th Infantry Division.

We left early in the morning, and after travelling by truck, we crossed the border into Germany… At last we felt that we were in the "Home Stretch". Little did we realise the three and one half months we were to spend in the town of Vossenack and the Hurtgen Forest, through the toughest part of winter, would prove to be the most difficult time for the men to survive. Now, actually being on German soil, we did encounter some German civilians, but not many. They were either very old, middle aged who were resigned to take care of their aging parents, grandparents or others to stubborn to leave their homes. It appeared that most of the German civilians retreated voluntarily with their soldiers. Later, as we advance further into Germany we wondered, how long they could continue pushing their people in front of them. The civilians didn't have much to say to us. Most of them were older women and daughters, usually in their thirties or forties, who had remained behind to take care of the elderly or the very sick. There were a few young boys and girls. At first they were frightened by our presence. I did my best to put them at ease. I tried to converse with them with the little German that I knew. They didn't seem to understand me fully. Likewise, I had trouble understanding them. Some of the very old German men we came across even got militant and threatening towards us. They appeared to be veterans of WWI. Secondly, they didn't like our sharing any part of their homes with us. Some G.I's acted very threatening towards them. I often had to step in and take the old men out of "Harms Way"… I tried to calm our guys by telling them that the older men probably had been soldiers in WWI who still had the old "German Military Discipline" in their blood. Besides, they were old soldiers who felt it was their duty to protect their homes and families. After all, they were now too old for the army, but patriotism and pride were still part of their being.

We hiked to the outskirts of Vossenack, Germany and spent the better part of the night bedded down in a wooded area. We were told to dig in, but few of us did, we were dead tired. Before daylight we moved into what was supposed to be a town. All that we were able to make out in the semi-darkness was a bunch of ruins. There wasn't a complete house standing. In fact it looked as if a tornado had preceded us and hadn't missed a building. We were told to find shelter wherever we could and to, above all, be very quiet and not to disturb a rock, board, or any part of the rubble. The Germans we were told had a full view of the town during the daylight from the hills surrounding the town. It was said, that they could see if anything had been moved or disturbed. If so, they would bring down a barrage of 88mm Artillery or Mortar shells on the area. We were to receive more enemy Artillery fire than we had yet encountered.

We crawled into the basements of the homes that had been levelled by Artillery or Mortar shells. We made ourselves as comfortable as possible in the ruins. We learned that the town had been a battleground between the Germans and the Americans over and over again, taken by one side and retaken by the other… on and on. So many Land Mines and Trip Wires had been strung by either side, that no one knew what area was safe to trespass on. During November and December of 1944 we also had to contend with heavy rains and snow. The paths that we ventured to travel during the darkness of night for rations, water, patrols, etc. got muddy or soft when the weather changed. One had to be sure to stay on the paths already travelled. However, when they became too soft or muddy Land Mines or Trip Wires could be tripped and a few of our guys got wounded or killed… Fisher got into trouble when he was returning (in a Jeep) from our company C.P. The road had been used many times but on this evening the road had thawed out a bit and the Jeep ran over a Land Mine. He was badly wounded and was taken to the Battalion Aid Station. This was the last that I was to see of him. He was greatly missed.

We had been told that the Germans would be looking down their Artillery barrels at us during daylight. The company C.P. in the stone church at the far end of town was about the only building still partly standing in which one didn't have to crawl, squat or stoop to get into or move about in.

We were shocked to learn on the night December 18th that the Germans had broken through in Luxembourg. Our only thoughts were of the G.I.s that had replaced us in Luxembourg. They had been through enough suffering in the Hurtgen Forest and were supposed to be recuperating….

Most of our activity was done at night, that was ammunition supplies, food, evacuating the wounded, getting replacements and some patrolling. At first the patrols usually left just before dawn but the creeping of daylight brought about more casualties. At first the order would come down from our company C.P. Or maybe from Battalion Headquarters for a Rifle Squad to patrol the deep draw between two high hills. This always proved to be a disaster. Only a few of each patrol ever returned. Patrolling the draw was suicide. We of the Weapons Platoon really felt sorry for the men of the Rifle Platoons. We knew that their mission was like going down "Suicide Lane"… The patrol was ordered by Battalion to be increased to two Rifle Squads plus one Mortar Squad.

The Mortar Squad was housed in a basement of a house that had been reduced to rubble. We had moved some boards to enter the basement and had replaced them exactly as they had fallen whenever we entered or left the basement, or "Rats Nests" as we got to call it. Disturbing the rubble, as already mentioned, could cause the Germans to notice and a rain of Artillery shells would follow.

Early one morning, the order came through that a Mortar Squad was to accompany a Rifle Platoon up the draw. This time, the squad was to be mine, as I learned later. I was sleeping soundly when the order came through. Miller, who by now had become a Mortar Squad leader, didn't want anyone to wake me so he volunteered his squad. When I awoke it was too late as the patrol had already proceeded up the draw. About a half an hour latter we heard the familiar sound of German Machine pistols and some German 88mm shells being fired. The patrol finely returned carrying wounded riflemen. The Mortar Squad had stayed well behind the advancing Riflemen, as was normal, to give them overhead firepower, also returned minus Miller and his Assistant Gunner. The story told to us was that Miller had set up his Squad's Mortar behind a standing brick wall. He had decided to use the wall as cover to screen the flare of fire that accompanied the tail of a Mortar shell as it left the barrel of the Mortar. The flare is especially visible in the dark or at the break of dawn. His Assistant Gunner dropped in the Mortar shells. After a few rounds had been fired, a German 88mm shell zeroed on them both and the brick wall collapsed on top of them, killing them both. His men said that they had managed to dig both of them out but they were dead. I wanted to go to where the bodies were to make sure that they both were truly dead. I was told that Medics had already removed their bodies to the rear. I was to wonder in the future if the men had actually dug the bodies out from under the rubble or did they take off like a shot when the 88mm shells came in and the wall collapsed. The details we received from the Riflemen and the members of Miller's squad were scarce and confusing.

I felt very bad for what happened to Miller and his Assistant Gunner. It was my Mortar Squad that should have accompanied the Rifle Platoon up the draw that morning. Not that the same thing couldn't have happened to me, and my Assistant Gunner. (Usually the Squad Leaders in the Mortar Section took over the First Gunners position when we were in the attack. Reason being that the Squad Leader was usually more experienced. The Squad Leader had a Corporal's rating). Maybe I would have chosen a different spot for setting up the Mortar. But at least, it would have been me, and not Miller who paid the price… Miller had a wife and child waiting for him back in the States. I had no such responsibility. I could never figure out why it had to be Miller and not me. He was a fine, kind, generous, young (20), faithful and religious person.

Well, the patrols through the draw continued almost every morning and the Germans, by this time, were waiting for them. There never appeared to be any advantage to our side as the G.I.s continued to get wounded and killed. The patrols were hammered by 88mm Artillery, German Machine Pistols, Mortars, Landmines and Trip Wires. Our attacking force was increased from a Rifle Squad with Mortar assistance to a Rifle Platoon with Mortar assistance. This only made an easier target for the Germans looking down our throats from the higher hill, which they occupied. I'm sure that the Germans must have believed the attacking forces were "Suicide Squads".

The Mortar Section continued to give supporting fire to the Rifle Platoons on patrol. My squad was attached to the 3rd Rifle Platoon. During one patrol, I had our Mortar set up in the bombed out basement of a bombed out house. As the Riflemen preceded us down the draw, we laid down a few rounds of 60mm Mortar shells to keep the Germans seeking cover. Well, it didn't take long for the German 88mm shells to start zeroing in on our position. The chimney of the house used was still standing. The base of the chimney had a large steel door about three feet high and two feet wide. When the 88mm shells started coming in Mac opened the steel door and was ready to crawl inside. However, it was stuffed with suitcases, and when Mac removed them we heard the sound of glass. Mac squeezed himself into the base, as much as he could, for cover. The fire of the 88ths on us ceased. We didn't care why, we were just glad that they had ceased in time. Our curiosity got the best of us and we opened the suitcases and found them full of different kinds of liquor. Boy… Mac's face lit up like a Christmas tree. I hadn't seen him so happy since we left the States.

We took the suitcases back to our cellar and Mac, the experienced Bartender, began to re-familiarize himself with his trade. He used sugar and lemon powder from our "K" rations, and he mixed many kinds of drinks that we had never heard of for that matter, I believed they were drinks that Mac had never heard of or mixed before. In other words "Mac's Specials". Believe me, there were a lot of drunk and sick G.I.s in our cellar that night.

Because all of our movements had to be done at night, supplies, replacements, etc. the only way that the Germans could see our movements was by firing Flares. However, they either were short of Flares or were quite desperate to see what movement was occurring because at times during the night they would turn on a powerful floodlight and shine it down the main street of Vossenack. It would stay on for about twenty seconds and then go off. It was very far away, too far for us to knock it out of action. If anyone happened to get caught in it's bright beam he would remain frozen in his tracks in order to not be detected.

Before dawn, one morning one of our company Lieutenants who had just come back from Battalion Headquarters spread out a map, saying to us that playing games with the Germans was over. Games? He said beginning tomorrow morning the whole of "C" company will take off on the attack, attacking the lower hill that is overseen by the higher hill in back. This higher hill was where the Germans were dug in and had a birds-eye view of us and the town of Vossenack. The Company Rifle Platoons were to dig in just below the crest of the lower hill. The idea was that as soon as the Riflemen consolidated their position they would gradually move forward and drive the Germans from the higher hill. Saying, "This is our objective and we will take it at dawn", he quickly scooted back to his Jeep and the safety of a captured German Pill Box at Battalion Headquarters.

This First Lieutenant had been with our Battalion from the States. He had been transferred to our company just before we left for Northern Ireland. He was young (around 24) skinny, flighty, kind of stuck on himself and didn't associate with us "Dogfaces". It was said that he was well voiced in Japanese. It was also said that his father was a Missionary in Asia. I could never understand why he was in the European Theater and not in the Pacific. Actually, one could never get close to him or be friendly enough to find out. Incidentally, I told the Lt. that I thought that it would be suicide to try and take the hill with only one Rifle Company. He just looked at me and said, "That's our mission".

The Mortar Section was to remain behind on the outskirts of town, at the bottom of the hill to be taken, in order to give supporting fire as required by the Rifle Platoons. I thought this to be a very sensible decision. If each Mortar squad was attached to each of the three Rifle Platoons that were going across a thousand yards of open fields and then up the side of a hill, we could get pinned down with the Riflemen by enemy fire, and be unable to set up the Mortars for supporting fire. Also a new supply of Mortar shells would be more available at the edge of town.

Well, "C" company took off, slightly before dawn, for the crest of the lower hill. There was one tank provided as support. As the troops advanced there was heavy fire mostly from German 88ths. Some of the Riflemen took cover behind the tank, but not for long. The tank turned tail and headed back towards town leaving the Riflemen dangerously exposed. There were many casualties before the company retreated back to town. Finally the whole of the 1st Battalion was ordered to move out in a frontal attack on the crest of the lower hill. They succeeded but at a great loss in wounded and dead soldiers.

"C" company Rifle Platoons dug in below the crest of the hill. They were pinned down and had great difficulty digging in. They were continually under heavy German 88mm Artillery fire. The Mortar Section had communication with the Rifle Platoons and our company C.P. We were standing by ready to give 60mm Mortar fire where and when needed. At night the Mortar Section pulled Guard Duty around our Battalion C.P. There was very little request for Mortar Fire from our company on the hill.

After a week of the Mortar Section standing by, Cortez, who was Section Sgt., called all of the Squad Leaders together. He said that orders had just come through from Battalion that our Mortar Section was to join our company on the hill. I asked Cortez when we were going to join them? He said, "within the hour". I said "Cortez, either you are just kidding or you misunderstood the order". It was broad daylight about 2.00 p.m. I told Cortez that it would be suicide to cross 1,000 yards of an open field and an additional 500 yards up a bare-ass hill under the eyes of the Germans and carrying our 60mm Mortars and ammunition. I said that we, at least, should wait until dark. Cortez replied, "Sorry George but those are my orders, we move out in an hour".

I could only conclude that Battalion reasoned that the rest of "C" company had advanced across the open field and up to the crest of the hill in almost the light of dawn, so they could see no reason why the Mortar Section should be the exception. True, but the Rifle Platoons and our Light Machine Gun Section had reached their objective at great cost. We, of the Mortar Section, were more than able to give supporting fire from our position at least until nightfall. Why take the chance of losing more men by a mad and unnecessary dash in full daylight? Up until this time we had received no request for Mortar fire from the hill. I could only assume that due to the losses the men on the hill had suffered that our appearance would boost their moral.

Well, in one hour we were ready to move out. I told the members of my squad to keep their eyes focused on the crest of the lower hill, to travel as fast as they could and to zigzag across the open field and up the hill. I also told them that under no conditions were they to stop or take cover in the shallow shell holes in the open field. The Germans had perfect observation of the field from their advantage point on the higher hill above the one where our company Riflemen were dug in. I told my men, including Mac, that it would be suicide to stop along the way.

The Germans had some 88mm Artillery but fortunately they had more 30mm Mortars, which weren't very effective unless they landed close or on top of you. I told my men that the only hope of making it alive to the crest of the hill was to move out on the double and to keep going in order to get under the shortage range of the German 30mm Mortar shells. This meant that the Germans could only fire their Mortars at a limited range because of the forest they were firing from. At times in the past, when we fired our Mortars, the Mortar tube almost pointed up in a vertical position when fired because the enemy had gotten so close.

Of course, we had to take our 42lb Mortar and all of the Mortar ammunition along with us. I grabbed my Squad's 42lb Mortar and took off running as fast as my legs would carry me, zigzagging across the open field. My squad followed close behind me widely spread out. Half way across the field, I looked back to check on my squad when I saw Mac had taken cover in a shallow shell hole. He wasn't wounded, just scared. I yelled to him, "Mac, get going, you'll get killed if you stay in that hole". He yelled back, "It's suicide to try and reach the crest of the hill". I just kept running and zigzagging, and as I approached the crest of the hill, I glanced back and could see that Mac had been hit. This was the last time I was to see Mac.

Those of us who reached the crest of the hill, where "C" company Riflemen were dug in, found that there were no Slit-trenches or Foxholes for us to occupy. The ones that were there were fully occupied by the Riflemen…80mm shells were coming in fast and deadly. I told my men to just dive into the nearest Slit-trench occupied or not. We just simply piled in on top of the Riflemen. There was no time to argue.

As things quietened down, we tried to dig our own Slit-trenches. However, every time we started to dig the sound of our digging echoed up the draw to our front and the Germans on the higher commanding hill to our front would send in a barrage of 88mm or 30mm Artillery or Mortar shells. We had to dig our Slit-trenches by, "the stroke". This meant that one had to get out of the hole he was sharing with another Rifleman, scratch out a few shovels of dirt and when he felt it was time for Jerry (German soldier) to lob in a few shells, he would dive back into the shared hole, hopefully in time. We usually made it but some others didn't and were either wounded or killed.

It took days to dig a Slit-trench under these conditions especially when one had to cut down young trees to use as overhead protection on top of the Slit-trench. Cortez and I dug a Slit-trench for three. It was wide and about two feet deep with small tree trunks laid one on top of the other and held in place by short sturdy branches placed upright and embedded in the ground. This vertical structure extended above the ground on three sides, adding another two feet of height to our Slit-trench. We had a slit opening facing the enemy, which was at our head when we slept. This was so that we could keep a lookout for enemy patrols day and night. The other end was the main opening facing a much larger dugout or bunker. It was always jammed with Riflemen.

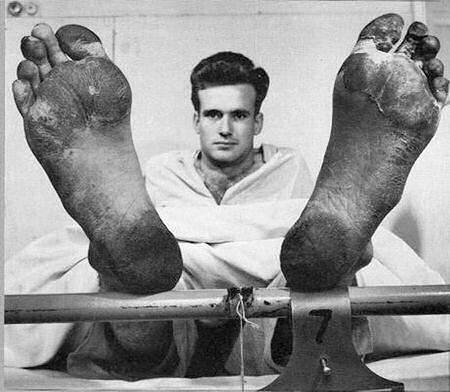

By this time, winter had set in and there was plenty of snow and very cold weather. All movement in our area was held to a minimum as the Germans still indiscriminately dropped shells on us at the slightest movement or noise. As a result, most of our movements were done at night. Supplies were brought up at night to the edge of our wooded area by halftrack. Our area must have seen plenty of action before we got there. There were German bodies lying around. Also the bodies must have been there a long time because they had turned black and there was that sweet smell of death in the air. Occasionally, I would see a G.I. going through the pockets of a dead German soldier, looking for souvenirs. This disgusted me, and I always put a stop to it. Once the sun went down the nights got extremely cold. Rifle patrols went out every night but they never seemed to engage the enemy. A lot of the guys in the company came down with, "Trench Foot" Because of the extreme cold and the restrictions to their being able to move around, ones feet began to swell up so much that they would look as if they were inflated. The feet would swell inside the shoes and some would have to cut or remove shoelaces for relief. In some cases, the G.I.'s boots had to be cut in order to reduce the pressure and the pain. Many of the guys were so bad off that they had difficulty just shuffling about for the bare necessities, food, mail, water, etc. In fact, some of the guys wouldn't even attempt to get out of their Slit-trenches or Bunkers because of the extreme pain they had to endure in trying to walk. Those of us who were still able to get around took care of their needs as best as we could. We brought "K" rations, water and mail to them. The only thing that they ventured out for was the "call of nature".

In spite of the fact that these G.I.s were suffering and would be almost useless in a combat situation they were kept on line as we were extremely below strength and continued to suffer casualties almost daily. Actually those with, "Trench Foot" were sitting ducks. I daily argued with our 1st Sgt. and company Officers to get the men with the worst cases of "Trench Foot" back to our Battalion Aid Station while there still remained a chance for them to be treated. I had very little success. I finally decided to get them off of the line by involving my buddy, Tex, who drove the half-track that brought up our nightly supplies. When he was ready to return to our Battalion Supply Depot with the wounded, if any, plus extra rifles left behind by the wounded and empty water cans. Cortez and I would help two or three of the men with the worst cases of "Trench Foot" aboard the half-track and have Tex drop them off at our Battalion Aid Station. None of them ever returned, at least not to our company. I saw a lot of my stateside buddies for the last time after helping to load them on the half-track….

How did Cortez and I get away with doing what we did? Well, our company C.P. once again chose to use the Mortar Section to provide security around the C.P. Bunker. It was a very large Bunker so it accommodated our Company Commander, company Officers, Platoon Sgts., believe me, not many of this group ever set foot outside of the Bunker. They usually sent the company runner outside to deliver orders, such as patrol schedules or for food and water. Not to brag or to impress the reader but Cortez and I did most of the running around on the hill for the C.P. We, from time to time received replacements, I would locate them in one of the many empty Slit-trenches vacated by the wounded or dead. Of course, I wouldn't tell them that….. Most of the replacements were very young (18 to 20) and had never been in combat. I thought….. what a hell of a place to indoctrinate them…. Most of them were brought up aboard the half-track at night or on foot just before dawn. I was shocked to see that they had full barracks bags with them. For some unknown reason they must have believed that they were going on an outing. Some barrack bags contained: fancy framed pictures of their wives, sweethearts or mothers, and some had leather-bound writing tablets. Some even had musical instruments with them. I had them keep all of the articles except the writing tablets in their barrack bags, telling them that they would have little use for the rest…. for the time being. I then placed the barrack bags in one location and covered them up, the best that I could, to protect the contents from the rain and snow. I used raincoats that had been left behind by the wounded or dead to protect them from the weather. I told them when we got to leave this "Hell Hole" that they could take out with them whatever they wanted. Believe me, these were truly green kids…. No one stopped to pick up anything when we did pull out. We were too dam glad to be able to get ourselves out….

As already mentioned, Cortez and I were mostly the ones to take care of all outside activities. We seemed to always be lucky enough to just be one step ahead of the German 88mm shells and 30mm Mortar shells. Maybe it was because we had come this far in combat and had developed a sense of what to expect. Our ears had grown very sensitive to the sound of the incoming 88mm shells. We both knew that being up and about, especially during daylight, was dangerous, but we both felt that someone had to be willing to take care of the men and other situations. The company C.P. depended upon Cortez and I to take charge of replacements, ammunition, rations, water and mail and to see to it that it was distributed. We did, at times, have some quite close calls.

The question might be asked, how come Cortez and I didn't get "Trench Foot"? The only answer I can give was that we moved around more than others. While Cortez was on furlough to Paris, Carter and I shared a Slit-trench. There were two Rifle Squads down in the draw to our front. Their job was to give the rest of the company ample warning in case of a German attack… day or night. They were a listening post to our front. The Riflemen had an elaborate set up all around them of landmines, trip-wires to set off landmines, hand grenades attached to trip-wires and encircling bobbed-wire. I'm sure that they felt very secure, perhaps too much so. Well, we at the top of the hill also felt secure. We felt that there would be ample warning if the Germans were on the move. We had, I guess, become as complacent as the Riflemen. We had forgotten the most important rule of a good soldier, "Never depend on someone else for your safety". At least, from this time forward this would be my primary rule….

Sgt. Grimes, who had been our Platoon Leader both in the States and Northern Ireland, whom we all felt had deliberately broken his ankle to keep from going into combat, suddenly appeared on the scene with our replacements. He was still a Sgt. and now was in charge of a Light Machine Gun Section. In reality, he didn't stop except to wave hello. He proceeded through the C.P. area, leading a Machine Gun Section plus he also was carrying a Light Machine Gun on his shoulder. His detail was sent to reinforce our Rifle Squads in the draw. We always considered him as having chickened out as so many of the regular Army men we had soldiered with had done. They were always bragging to us how they would show us how to win a war. Well, I was dam glad that they never got the chance…. However, it seemed as if Sgt. Grimes was about to show us. He seemed anxious, smiling and happy to be in combat. I guess we were wrong about him? In fact, his presence as part of our outpost made us feel more secure than ever. We knew how G.I. he had always been and he gave much attention to detail and strict enforcement of Army regulations. He would most certainly see to it that the men on outpost duty would stay alert…

One morning, as Carter and I shared out Slit-trench, a German patrol worked its way up the draw to our front, which was being manned by our outpost with all of its safeguards and troops. We heard no warning or shots of resistance. Before we knew it the patrol was heading for our Company C.P. I heard some firing from the Riflemen dug in on line. It was real early when the patrol appeared and some of the troops were still asleep or preparing their "K" ration breakfast. Carter and I looked through the small opening at the head of our Slit-trench facing the enemy. We saw about 12 Germans coming towards our Slit-trench. It would have been suicide for Carter and I to stand up and face the 12 Germans coming towards us. We were completely surrounded. We fired at the oncoming Germans from the opening at the head of our Slit-trench. I had a 45 Cal. Pistol, a 30 Cal Carbine and a German Luger. Carter had a 30 Cal. M-1 Rifle. In our Slit-trench we, at least, had some protection without exposing ourselves. Suddenly, we heard a burst of fire from a B.A.R. (Browning Automatic Rifle). I said to Carter, "Well we have someone near with plenty of firepower". We were more or less trapped in our Slit-trench. I was afraid that shortly a German Potato Masher (German Hand Grenade) would be coming through our frontal opening. I said to Carter, "Well, I guess this is it". With all of the firing going on around us, we were sure that a large German force was to follow on the heels of the German patrol. All that I could think of was "What in the hell happened to the warning we were expecting to get or hear from our outpost"? Just as soon as the whole incident was over, Carter and I got out of our Slit-trench to look around. There were no dead G.I.s just 3 German soldiers. One of the soldiers had his head bashed in and the other two were badly shot up, all three dead. The one with the bashed in head, we learned, had passed by a G.I.'s Slit-trench without seeing it, we assumed. The G.I. was so shocked to see the German go by without noticing him that he just reached for whatever was handy, which was his entrenching shovel, and beat in the German's head from behind. We asked why he didn't use his M-1 Rifle, he said, "I didn't want to shot him in the back"… I guess the G.I. had seen too many westerns where the bad guy often shot the good guy in the back in a cowardly fashion. I guess head bashing was more fair. As stated before, I never saw a German soldier who was wearing a steel helmet, just a peeked cap, making it easier for someone to beat his head in, I guess.

A lot of the troops were still asleep when the attack occurred and they were just as surprised as Carter and I were. I guess we all were depending on our outpost to give us ample warning. In our sizing up the result of the attack we came across the body of our Battalion Commander. It seemed that someone in the German patrol had picked up an American B.A.R. which had been placed on top of a stack of odds and ends to go back to Battalion that night when Tex and his half-track came up with our rations and other supplies. We found the B.A.R. lying next to the Battalion Commander's body where the German had dropped it. Occasionally, an Officer from Battalion would come up to our position before the crack of dawn and talk to our Company Commander or whoever was still able to be in charge. 1st Lt., 2nd Lt., First Sgt., etc. I assume that the Battalion Commander had come up to our position to size up our situation.

After the smoke of the battle had cleared, I took a couple of Riflemen and a few of my dependable Mortar Squad buddies down into the draw to find out what had happened to the men of our outpost. I was familiar with the warning signs of mines, trip-wires, etc. set up around the entrenchment. I was part of the detail that had helped to set it up. I told my men to remain on the alert as part of the German patrol might still be in the area. Actually, I expected to find the members of the outpost knifed or strangled to death in their holes. I felt that those who were to have remained alert on a two hour basis had been surprised or fallen asleep. This was the only reason I could believe for them not having given a warning.

When we reached the forward position, we found everything intact. There wasn't a wounded or dead G.I. to be found. We never did figure out how the German patrol managed to get through the land mines, trip-wires and barbed wire without being detected. Maybe our men were surprised by the Germans and had been given a choice of either dying in their holes or manoeuvring their way out safely and surrendering. Perhaps, the Germans had been watching the path through the entrenchment taken by our daily re-suppliers thus, able to approach the men within the entrenchment without firing a shot.

Upon reporting to our C.P. what we had found and the situation in general, I continued to survey our rear defence area for any wounded or dead G.I's. I came upon a Slit-trench that was above ground. It was more or less dug into a small hill. A bulging barracks bag was blocking the opening. I kicked it inward and I found a G.I. that I had never seen before crouched against the back wall with a frightened look on his face. I said, "What the hell are you doing by completely blocking your means of observation"? He replied, "I'm cold and trying to keep warm". I said, "You are here to defend our position, to see and kill Germans, not to hide from them".. H must have been in his late thirties or early forties. After taking a good look at him, I began to feel sorry for him. I said, "What in the hell is a man of your age doing here"? He answered that he had been a baker in the Army in the States and had gone A.W.O.L. and as punishment he was shipped off to combat… It sounded like something the Army would do. That night I sent him back to our company kitchen with Tex.

There was an Officer who had joined our company as a replacement. He was one bag of wind, a bragger and all around S.O.B. He spent most of his time at Battalion Headquarters in the bunker. Well, this morning after the attack he came storming into the large bunker which had been fairly emptied due to Trench-Foot and Dysentery. Cortez and I had moved into it after Carter had been sent to the rear due to Trench-foot. The Lt. had three replacement Officers with him. He yelled, "You yellow S.O.B's. you allowed a Col. to be killed with one of our own B.A.R's. Well, we are going to take the higher hill to our front… NOW… None of our company Officers or Sgts. housed in our C.P. Bunker accompanied him. Either they didn't want to leave the security of the bunker or they had already given this bag-of-wind permission to do whatever he wanted to do. I'm inclined to believe that he never got permission from our C.P. or he showed them that he was sent up to take charge of the situation. I said, "Lt., we don't like the fact that the Col. was killed anymore than you do… It happened through a surprise attack without a warning from our outpost".

Trench Feet

He had all available men spread out in a skirmish line. The new replacement Officers joined us. It was their first experience in combat. 2nd Lt. Scott was at my side (one of the new Officers). We all advanced down the draw. Our mission was to take the higher hill by either driving the Germans from their advantage point on the hill or take possession of the hill and capture as many Germans that we could. I told Scott, as he had told me to call him, that we had been trying for a very long time to drive the Germans from the hill. That when we were much stronger in numbers, stamina and moral we were unable to accomplish this objective. Scott and I continued to advance on line. After we had gone about 300 yards we were pinned down by German Mortars and Machine Pistol fire. At this point, I looked to my left and then to my right to see how the rest of the skirmish line was doing. To my surprise I discovered that Scott and I were alone fighting the battle. There was no one else in sight on either side of us… I quickly brought this fact of life to Scott's attention. He said to me, "Well George, what do we do now". I said, "Go back to where we came from, if we can make it". I was shocked when he replied, "No, our mission is to take the hill to our front". I asked, just you and I. His answer was "Well, if we are all that there is, I guess we will have to do it". I thought boy, this guy is off his rocker. But, I could also see that there was no way I was going to change his mind. I wouldn't think of disobeying a direct order from an Officer, even if I thought it was dumb. I said, "O.K. if you think we should give it a try, let's go". Well, we both ran forward crouching, zigzagging and taking advantage of any cover in our path. We had gone about a hundred feet and all hell broke loose. We were pinned down with bullets all around us. I turned to Scott and yelled, "Do you still want to take that hill"? Scott replied, "What do you think we should do"? I answered, "Why don't we try to make it back to the bunker"? He said, "O.K." I told him, "I'll cover you as you run back taking cover as you go. Don't go any further than a hundred feet at a time and then hit the ground. Then you cover me as I work my way back to where you are. Then we will alternate in this fashion until we are out of the range of enemy fire. As I worked my way back my carbine stock must have grazed a low bush and I almost dropped it.

Well, we finally made it to our bunker and seated way back in its farthest corner was our big mouth, Lt. Stark. I learned later that he had not even left the bunker. I gave him a dirty look and I'm sure he knew what I was implying. He was that yellow S.O.B. that he had the nerve to call us earlier. As I settled down in the bunker, Lt. Scott asked me what happened to the stock of my carbine. When I looked, I noticed that the lower right hand side of it was broken off. The only reasoning that I could come up with was that as I was falling back 100 feet at a time the stock of my carbine jerked. Actually, it must have been struck by a German bullet. Believe me, after a deep swallow, I thanked the Lord…. Lt. Stark and I were to tangle again in the future. But for the present he beat a quick retreat back to his Battalion Headquarters Bunker. I don't think he liked the idea of being so close to the enemy. He would much rather "go backward, than forward". As far as I was able to determine, most of the men who started out on the skirmish line returned safely to their Slit-trenches or bunkers. I never did see the other two replacement Officers again. They might have been captured, wounded, killed or returned to our Battalion Headquarters.

Things remained sort of calm for the next few days. Lt. Scott and I became good friends. He showed me the 45 Cal. Pistol that his father had given him just before he left the States. His father had been an Officer in WWI. Scott also had an Automatic 30 Cal. Carbine. It had been made automatic because he had filed off part of the trigger housing.

Early the next morning a large force of G.I.s from the 77th Division joined us up on the hill. I was glad to see them. I thought at last, our relief. I was wrong. I learned that they were to pass through us and to show us how the higher hill to our front should be attacked and taken. Well, all of us of the 1st Battalion of the 28th Infantry were more than happy to have them achieve their mission. They took off down the often- travelled draw to our front. We stayed behind in our Slit-trenches and bunkers wishing them luck. In an hour as Lt. Scott and I, others sat inside the large bunker we heard a lot of shouting going on outside. We could hear G.I.s shouting in English and getting some responses in German. I glanced out of the bunker and saw some Germans lying on the ground and the G.Is. yelling at them to get up. I could understand why the Germans refused to get up because all the noise or shouting going on was sure to bring 88mm shells in response. The G.Is. weren't smart enough to realise the danger they were in as they hadn't been in the area long enough to know about the resonse any noise had caused in the past. With all of the yelling going on, it caused the German artillery to pinpoint the target. All of a sudden Lt. Scott said, "I'd better straighten out those stupid G.Is. before they get us all killed". Apparently, these G.Is. of the 77th Division weren't as experienced in combat as we thought. Maybe they didn't realise how their voices can be carried up and down a draw. Lt. Scott grabbed his carbine and left before I got a chance to warn or stop him from dashing out of the bunker into the line of the artillery fire. I hesitated following him immediately as I had to borrow someone's rifle because mine had been partially shot away. Well, that few second's delay saved my life.

As Lt. Scott got clear of the bunker's entrance, a German 88mm shell landed close to the entrance. The concussion blew me, with great force, against the back wall of the bunker. I was stunned for a minute or two, and when I became steady on my feet, I took off out the entrance. About ten feet from the bunker I stumbled over the body of Lt. Scott. He was dead, having been killed by the concussion and shrapnel from the German 88mm shell that landed close to our bunker. I was shocked, depressed and had a severe pain in my gut. I then ran over to the Non-Com. In charge of the prisoner detail and said, "You stupid S.O.B. you don't have half of the brains that the German prisoners have. They knew enough to hit the ground and to keep quiet when their own artillery shells were landing all around them. You kept yelling at them to get up. Do you know that you caused the death of a dam good American Officer"? I could also see that some of the G.Is. and German prisoners had been wounded or killed by the shell.

I covered the body of Lt.Scott with a blanket until I could have his body moved out that evening on the half-track. I took his Automatic Carbine, as mine had become useless. I believe that he would have wanted me to have it. I also decided to take his 45 Cal. Pistol so that if I ever made it back to the States I would try to find his father and return it to him.

The fighting went on for many months after we left the forest area. But, nothing compared to the hardships of the Hurtgen Forest Campaign, and on March 4th 1945 the announcement of the final surrender of all German troops was made.

We knew that the war was really over when we were sent to "Camp Old Gold", an embarkation point. While there, I decided that returning Lt. Scott's 45 Cal. Pistol to his father may not be the thing to do. If Scott's father was still depressed about his son's death, he might use the gun on himself. I gave the pistol to the Company Officer.