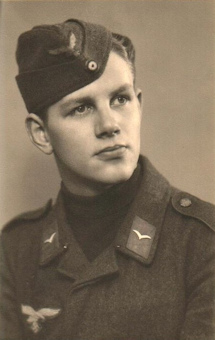

6th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment

The warm weather continued and we used every opportunity to have a swim in the Baltic. Just about finished with our training flights, except for blind flying school (flying by instruments only), the "further training" stopped because of the acute fuel shortage. We were given the option of joining other army units, for example the division "Herman Göring", which was a glorified infantry, or the tank corps or the fighter pilots. If we failed to make up our minds, we would simply be sent to the infantry in Russia! Almost everybody opted to be a fighter pilot, thus remaining "Flying Personnel". The other contributing factor was the expectation that pilot training would take considerable time, by which the war might well be over.

We were told that, failing to shoot down an enemy bomber, we would have to ram it, but eject and parachute down to earth before actual contact. A quote from the book, "I Fought you from the Skies" by Willi Heilmann, describing action in which he was involved (from the invasion of Normandy until the end of the war), describes what actually took place.

August came and we were to be transferred. After a day on the train, we landed in Gardelegen, a small town near Magdeburg, with the paratroopers (!). On being asked whether I would be willing to jump, ie, training to jump, I answered, "I did volunteer for the 'Flying Personnel'." I was told: "We are 'Flying Personnel'", which, strictly speaking, is true. So I became a paratrooper!

We changed uniforms and at once looked like paratroopers. Our new uniforms consisted of a different, shorter, jacket, the pants were buttoned on the bottom and we were issued with lace up boots, extending above the ankles. The pants had a buttoned up pocket on the outside, just above the knee, for the Kappmesser, a knife with a retractable blade to be used in case of tree landing to cut oneself loose. In the event of hand to hand fighting, the knife would became a weapon.

Soon after, I was seconded to the 6th Paratrooper Regiment, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel von der Heide. The regiment had come back from the invasion of Normandy, where it had suffered huge losses and we were to replenish the numbers. We went to Mecklenburg, near to the town of Güstrow, where we encamped on a large estate. Here we were trained to operate eight centimeter mortars. There had been rumors that we would soon go to jump training, but it did not eventuate. One early morning we marched to Güstrow Castle, where the regimental commander held a speech, exhorting us to fight "to the last man". Amongst other things he said: "We shall fight before Berlin, in Berlin and behind Berlin, and the last soldier keeping the banner aloft will be a soldier of my regiment!"

It wasn't long before we were called out and our company chief addressed us, saying: "Comrades, the fronts are burning, and the enemy is closing in on the Fatherland. The time has come to go into action!" The stores were opened and we were issued with steel helmets, rifles, pistols, a combination of weatherproof drill which had many pockets and buttoned up under the crotch; we called it "Knochensack" (bone bag). Weaponry and ammunition was taken to the train; we had to walk to Malchin, approximately five or six kilometers.

The journey took us via Hamburg to Holland where we got off at Tilburg, close to the Belgian border. The front was on the Dutch-Belgian border, near Beringen on the Albert Canal.

For the first time I heard the actual artillery bombardments, that is, the sound of the grenades. They were, however, quite a distance away.

Our task was to keep the enemy back as long as possible so that other units could reorganize themselves. We gradually withdrew, and crossed the border back into Holland to take up new positions, amongst them Goirle, near Tilburg, where we had dug our holes to shelter us from artillery bombardment. We were located in a pine forest and were in the process of chopping down young pine trees to cover our dugouts, when all of a sudden we came under intense bombardment from British tanks. There was practically no shelter, so I lay head to head with a comrade in a very shallow depression, a sort of drain along the road. No need to tell that I was scared to death! During a brief pause we looked at each other and, to my amazement, I saw my mate laughing like anything! He was just as scared as I was but, while I was nearly crying, his emotions and tenseness found relief in laughing. His name was K. We then ran across the road and dived headlong into our holes. Later we picked up our gear and retreated.

The advance of the British had slowed down somewhat, and we went into action near a small town called Schijndel. We positioned ourselves in an orchard, digging in between pear trees with the most beautiful, juicy, large pears, almost hanging into our dugouts. We really feasted but, on the negative, the fruit had an impact on our bladders, so that we had to relieve ourselves quite often.

Incidentally, the German mortar had a maximum range of 2400 meters. This was achieved by putting accelerator rings around the rather long shaft of the mortar bomb. The enemy did know of course what our mortars were able to do, but what they didn't know was that we used French mortars and Russian bombs, or vice versa. The difference was that the barrels of these mortars were longer, as were the tails of the Russian bombs. This enabled us to attach two or more accelerator rings to the shaft, making the distance around two hundred meters further. When they tried to give us a hiding, believing we were 2.4 kilometers away, their bombs landed well short of the target!

During that time the airborne troops of the allies started their campaign to land at Arnhem, in an effort to secure a bridgehead over the river Rhine. This is depicted in the film, "A Bridge too Far". They came by their hundreds, with larger aircraft having transport gliders in tow. Our neighboring unit, armed with the M.G. 3000 (that is, 3000 rounds per minute!) (the enemy called it the "Adolf Hitler Saw"), shot down one of the aircraft which came across well after the others had passed.

The British got a hitting at Arnhem, especially by the German Panzer Division which had just taken up the position in that area.

A little later we were moved to Bergen op Zoom, where we dug in south of the city, near the town of Hoogerheide. The town is situated at the mainland end of a very narrow strip of land, approximately two to three hundred meters wide, connecting the peninsula of South Beveland. There were several thousand German troops stationed there, who had little chance of getting out, since the British artillery controlled that narrow strip of land. The British were supposed to have about a week to break through, but were held back for about three weeks. No wonder we were called "die Feuerwehr von Holland" (the "Fire service of Holland"), since we were sent to all the "hotspots". Others called us "Kriegsverlängerer" ("War Extenders"), for rigid resistance would prolong the war. A lot of troops were eventually evacuated from the peninsula by "storm boats", little open nutshell-like boats, with outboard motors. Today all the little islands in the Rhine delta are connected by roads across the water.

We withdrew in November, crossing the Waal, one of the arms of the Rhine at Willemstad, where we had one last encounter with the British. We then gradually left Holland and crossed the border into Germany near Wesel.

No sooner had we got there than the drill began once more. After ten to twelve weeks in action we had to "learn" how to fire a mortar bomb! They didn't even de-louse us! Heaven knows that we had lice, or rather "the lice had us"! After a couple of days we were shifted south to Elmpt, near the city of Mönchen-Gladbach, on the Dutch border. We were billeted in the township and I, together with a sergeant and one other mate, stayed in a "four sister house." One of them had been married but was widowed, and the other three were Fräuleins but, alas, well into their late sixties! "Such is life!"

Our favorite pastime while we were with the sisters was to undress after the ladies had retired upstairs, and pick the lice out of our singlets. They were head to toe along the ribbing, virtually by the hundreds. There was a large fuel stove in the kitchen, and it delighted us to put the lice on the red hot stove to see them pop!

In the Elmpt forest we dug in once more. The action was near Roermond, just a few kilometers away on the Dutch side of the border. For the first time I heard the Stukas, short for Sturzkampfbomber (dive bombers) in action, bombarding the British forces. It was a scary experience, and I can't imagine what it did to the actual enemy!

Once we were de-loused. This consisted of a shower, a spray, and new underwear and shirt, but it was a matter of a few days and the lice were back. Afterwards I found that my wallet and parcel stamps were missing, as well as over 300 Reichsmark, pay for nearly three months. The money didn't worry me much, but the two parcel stamps, which were to be sent home so that I could be sent a parcel, were a severe loss.

Soon the good times were over, and we were once again on the move, this time by goods train. We came, I believe, through Köln at night, then went on to Weilerswist, about twenty kilometers south of Köln, where we disembarked. Here we met the S.S. troopers who had been in action during the invasion of Normandy by the Allies. They had been back in Germany since July/August, and wore their best uniforms. When they saw us they laughed at us, for we wore our battleworn battle dress. One of them announced: "By Christmas we will be in Paris." My reply: "Yes, probably as P.O.W.s", didn't go down too well, for he reached for his pistol, but thought again and did nothing!

We were driven by trucks to the Eifel, a mountain range along the Belgian border. Here the American forces were our enemies. We disembarked at Froitzheim, near Düren, and marched to Untermaubach where we dug in. This was a rather difficult task, as the ground consisted of slabs of slate which always collapsed once one got to about one meter in depth.

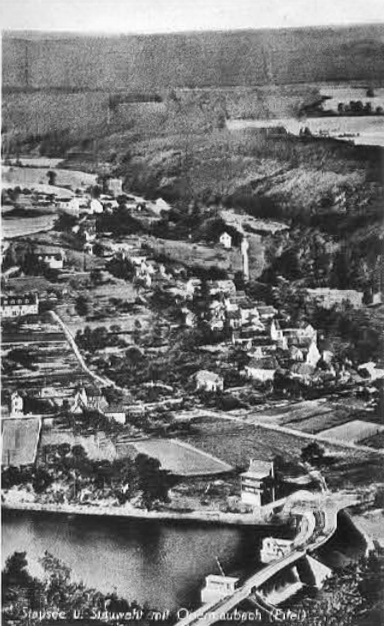

Obermaubach

On we went to Obermaubach with the big storage dam. Here we had established a bridgehead on the west side of the dam. Nearby was the Forsthaus, the forester's lodge. It changed hands several times.

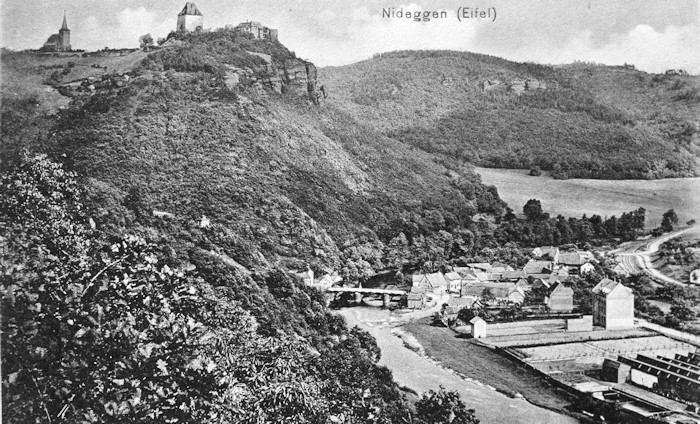

And again we moved on, this time to Nideggen, and took up positions there. The river Rur (not to be mistaken for the Ruhr) flows through the ranges in a south/north direction. The west side of the river was occupied by the Americans, and the east by us. Sometimes we could see the Americans tobogganing down the hills, we were that close!

The Roer river and Castle Nideggen

Toward January 1945 the fighting intensified dramatically but the overpowering might of the U.S. Army proved extremely difficult to combat. Ammunition became rather scarce, and food wasn't too plentiful either. The morale of the German army sank at an alarming rate and yet the fighting continued unabated.

By mid-February we were digging once more. We had established a bridgehead and prepared our future positions. This involved moving across the river by night over the bridge at Zerkall.

View from Zerkall

We worked overnight and returned to our position before daylight. Once, on returning, we suddenly came under mortar fire. We ran for cover toward a house, but before we reached it a mortar grenade hit the corner of the house at the spouting, sending shrapnel flying about. Of a group of seven or eight, one soldier received a wound to his thigh, another a rather large wound to buttocks and yet another shrapnel into the back and probably into the lung. K., who I mentioned before, was behind me and got killed. As for myself, I did not receive even a scratch! Because the ground was frozen rock hard, we could not bury K., so snow was piled up to cover him, and a rough wooden cross erected.

On February 28 the Americans were about to break through at Abenden, a short distance from Nideggen, and part of it, so the bridge across the river was blown up to make it more difficult for them to advance. During an artillery barrage we all went for cover in the nearby houses. One of the comrades and I sheltered in the basement of a house and found ourselves trapped as the entrance to the basement was blocked with rubble. After some hours we heard voices and these sounded quite unfamiliar. They were in fact Americans. After making a lot of noise they got us out, and we found ourselves in front of a dozen or more rifles pointed at us. Soon we were separated, no doubt because they feared that we would try to escape. To be frank, no such idea had struck me, rather I was glad that the war, for me, had come to an end.

Soon they took me behind the front lines to their kitchen, some fifteen to twenty kilometers away. I was rather scared when I was told to move downstairs into the basement, but was tossed a blanket and motioned to sleep. Sleep of course didn't come, and early next morning I was told to come up into the kitchen where I was given breakfast, the first decent meal for many weeks. I can only remember that amongst the other food there was a sort of hot porridge and real brewed coffee, probably the first real cuppa for years! Then there was chocolate and cigarettes. Conversation took place by means of sign language, but it worked.

On we went to the command post where I was motioned towards a pot belly stove to warm myself. One of the G.I.s tossed me an orange and I imagined that all my Christmases had come at once!

A little later that day I was moved back toward Nideggen and to my amazement I found that the roads had been repaired, ie, they had been graded. I realized then that we really had fought a losing battle. We had to carry ammunition and food, etc. for over one kilometer because of the road conditions which bore the marks of many artillery and bomb craters, and yet one day later the roads were smooth. The material superiority of the U.S. army was simply overpowering. Nideggen had fallen at the same time as Abenden.

Again we were transported, first by trucks, then by goods train, past Aachen to Namur in Belgium. In between we were fed in a huge mess tent. The feeding took place by lining up, being grabbed by the scruff of the neck by a 6' 4" Negro G.I. with the physique of Joe Louis, pushed on by another who handed out empty fruit or jam tins, being pushed past the servery where we got a ladle full of hot vegie broth, and being thrown out at the opposite side. There was nothing cruel about all this, as there were a great number of P.O.W.s to be fed. It simply had to be done quickly.

We eventually arrived at Namur, where again we were herded through a door into a huge building where a G.I. stood with a huge instrument, similar to an insect sprayer, pumping de-lousing powder down the back of the neck. This sent the lice berserk, and us too!

After a day or so we once again moved on, on to France and, I believe, via Paris to Attichy which is east of Compiègne, approximately thirty kilometers north east of Paris. Compiègne is the place where, in 1918, the armistice was signed in a railway carriage. In 1940, after the French surrender, the armistice was again signed in the same carriage, this time the Germans being the victors. Here we slept in tents, on earthen floors, but we had acquired a few cardboard boxes which we unfolded to use as underlay. The nights were cold but fortunately the days in early March were quite mild, even though it was still winter!

Again we moved on and arrived in Cherbourg where the same conditions prevailed! Here we did have to work in a stone quarry one night. From Cherbourg we finally were transferred to England. The day was March 21, the start of spring.

Submitted by his daughter Christine.

Many thanks dear friend Christine.