K Company, 110th Regiment of the 28th Division

Excerpt from "My Tour With the 28th Division" - Chapter 13

The Hurtgen Forest (Schmidt), Germany October - November 1944

The Hurtgen Forest, on first observation, looked like heaven. The dense forest, with its towering pine trees, looked like a place where the German artillery observers would not be able to locate us. In the hedgerows, it was a fight for each hedgerow, and the casualties were severe. The Siegfried Line, with its pillboxes, was another world. The pillboxes, for the most part, were in large, open areas. They were camouflaged and had excellent fields of fire, and German artillery observers could watch our movement. It always seemed that the Germans had the high grounds. On second observation, when we got into it, the Hurtgen Forest looked ominous. It was dark, and as we went to our positions, we could see some of the problems that the 9th Division faced. The pine forest, which composed 99% of the forest, was littered with branches, and it was difficult to go in a straight line because of all the debris. We noticed the trees were scarred from shrapnel, and many trees were down from direct artillery hits. In general, the forest floor was a mess. This was caused by what we learned to fear - the tree burst, which happens when an artillery shell hits high up in a tree, explodes and sends shrapnel raining down on you. The 9th Division and German dead were all over the area.

We relieved the 9th Division around the end of October.

The guide from the 9th Division mortar section took our 3 squads to their mortar position. They were forced to construct underground shelter against the tree bursts. These consisted of a dugout about 4 feet deep. The length and width I no longer remember, but I do know that you were always on your hands and knees. They were covered with layers of pine logs and dirt.

It had one entrance. There were a number of these covered dug-outs for all members of the three mortar squads.

This mortar position, made by the 9th Division mortar section, was completely surrounded by tall pine trees. The clearing did not have to be large, because of the trajectory of the 60mm mortars. This helped us from being observed by the enemy. We had telephone lines going to the three rifle platoons on the line and one forward listening post to the left side of our defenses. We never found out who was on our left, but I think the mortar section was in a gap between one of our other companies, but I have no proof of this. The sergeants took turns at the forward listening posts, a very lonely and scary job. Every time we changed sergeants on this post, you wondered if you would make it to the post. Because of all the debris from the trees, it made an ideal position for an ambush or a sniper. Secondly, you wondered if you were hit in this tangled mess, if anyone would ever find you. At this period of time, we had more mortar ammo than I have ever seen. There were cloverleaf canisters which held 6 - 60mm mortar shells piled up about feet high for about 50 feet, and there were no restrictions on the use of them.

If one of the rifle platoons asked for help, we checked on our firing charts and sent as many rounds into the German positions as was necessary. If a German was chopping wood for whatever purpose, we would send mortar shells into the area until the chopping stopped. We fired at night, so they couldn't sleep, the same as they did to our positions. During the firing mission, using 2 gunners to put the shells into the mortar tubes, one gunner put a shell down the tube before the first one went out.

But nothing happened, because the brass plug was not blown out on the side of the shell- a built-in safety factor.

60mm Mortar

Because our position was so exposed, and we were never told who was on our left or ahead of us, we decided to rig an alarm system, which consisted of empty K ration cans containing small rocks, attached to a line running around our complete area, so that if anyone hit the line, we could hear the rattle of the rocks and be alerted. We did this, because even though we always had sentries posted, your vision was limited at night in the forest. One night, between 11 PM and 2 AM, the cans began to rattle, and the battle started. We started throwing grenades out of our covered dugouts, and since we were scattered in the clearing, no one knew whether the explosions were friend or foe, and this continued for quite some time. In the morning, when we inspected the area, it was a mess. The ground was torn up, and more debris from the pine trees was present, most of it being redistributed by the explosion of the grenades. The fellows on the line must have thought they were being outflanked with all the noise and flashes from the explosions. We never found any bodies, so possibly some animal must have hit the wire, but it sure gave us a scare and probably others as well.

One time, when it was my turn to be forward observer, I started out to my listening post. The shelling had brought down the tops and branches of the pine trees, and the forest floor was a tangle of branches. The only way you could find the listening post was by tracing the telephone wires through the downed tree branches. Each time you went up to this post, you didn't know if you would be shot by a sniper or captured, because there were no GI's in front of our listening post. I never heard anyone to my right or left, so the post must have been in a gap in the lines. One of the times that I went up to this post, the Germans must have heard me coming. It was almost impossible to move quietly, because of all of the debris from the tree bursts. A mortar shell came down right in front of me.

I did not hear it coming (you never hear a mortar shell coming in because of the trajectory). It hit about 12 to 15 feet in front of me. The branches of fallen pine trees on both sides of me filled the air. Wind from the explosion gave me a wind burn, and the concussion forced me to the ground. I was covered with tree litter, and smoke covered the immediate area. I was sure that I was hit. I felt all over my body for the feeling of blood, but there was none. I was not knocked out from the closeness of the round, but I was dazed. I thought at this time that there was no way that I was going to survive, after all the close calls that I had, and most of my old friends were gone. I made up my mind that as long as I wasn't going to make it, I wouldn't quit either.

After coming back from one of these sessions at our listening post, we received a fire mission on a position in front of one of our rifle platoons. Since we had mortar ammo in ample supply, we decided to really do a job on the German position.

We got all set up, and 2 gunners and ammo carriers passing mortar rounds, put up between 25 and 30 shells in the air before the 1st round hit the ground. We were aiming at their bunkers. It must have been devastating. It really sounded great.

In this time frame, an attack was planned. Our weapon platoon Sgt. and the NCO of the mortar section went over the attack sequence. I was given a map of the area of what is now referred to as the Battle for Schmidt. We were never told what our mission was. In the attack, K Co.'s three rifle platoons were to secure an area 1,000 yards from our original position, dig in and hold. Using the map, I was to follow with the mortar section. There was a time given for the attack, but I no longer remember what it was. The artillery opened up, and soon after, the attack began. Our rifle platoon took off, but they were stopped before they had gone 100 yards, and they took heavy casualties. The mortar section never left its position. I heard that a request to the Air Force to bomb the German fortifications in front of our position was denied, because our positions were too close to the German lines.

After this attack failed, we were told we would be pulling out. Under cover of darkness, with what was left of K Co., we pulled back, and along with the remainder of our 3rd Battalion, became part of Task Force Ripple. After the war, when I was a civilian, I read about being part of Task Force Ripple and going to the aid of our trapped sister regiment, the 112th. Also, by reading from my collection of WWII books, I learned that our objective was the town of Schmidt and the Rur Dams, in particular the Schwammenauel Dam.

On the way to join the 112th Regiment, we went through Vossenack, a village in flames. It was late at night or early in the A.M.. It was just like you see in a war movie, smoke and fire all over. The smell of the burning buildings, gun powder, gasoline, and oil from burning tanks, and the ever present smell of death were very evident. The eerie light from the fires showed damaged buildings everywhere, and when a shell exploded, you could see a church steeple in the distance. It was during one of these flashes of light that I saw what was left of a GI who had been run over lengthwise by a tank. I could tell it was a GI because of his clothing - webbing, steel helmet, etc., a sad sight to see. There were many bodies in the village, both German and American, which you could see by the light from the fires as we passed through. Part way through Vossenack, we left the main road and turned right to pick up the Kall Trail.

The Kall Trail (In the Hurtgen Forest)

The Kall Trail

Click to enlarge.

Note: Above is an external link to the Ibiblio website,

and will open in a new window.

We went down into the Kall Valley and across a stone bridge wide enough for one vehicle. This part of the march to aid the 112th Regiment had less shelling, because the Germans did not know where we were at the time. A light but steady, cold rain was falling. After we crossed the bridge, we started up the Kall Trail. The trail was very narrow in spots. There were no vehicles with us, and we had to carry our 60mm mortar and ammo, which was very difficult because of the steep terrain. The Germans finally found us, and the shelling picked up. In combat you see many things that your eyes were never meant to see. The order of march for a rifle company usually is 1st platoon, 2nd platoon, 3rd platoon and the 4th platoon, which is called the weapons platoon. In combat we rotated the platoons. It was raining and starting to get light enough to see. A shell hit somewhere ahead, very close. When I got to the area, a shell apparently had hit the top of a tree (treeburst). There were 5 men hit. Four of them were dead. They looked like rag dolls that were carelessly thrown around. Their arms and legs were not in normal positions, and the medics had not arrived on the scene. As I came up to one of the men, he was in a sitting position, looking sort of in a stupor. I don't know if he was watching the water from the rain, along with his blood which had turned the little stream red. As I passed him, I looked at his face, but I'm thankful that I didn't recognize him. It had to be one of the fellows I knew, because of the line of march and the time element. I was able to look down inside of him, because of the large wound in his shoulder. I am quite sure that by the time I passed him, he was dead due to the depth of the wound. This all took place in a matter of seconds, but at the time, it seemed like hours.

My last days with the 3rd Battalion, 110th Infantry, were on the reverse slopes outside of Kommerscheidt, a short distance from Schmidt, Germany. With what was left of the 3rd Battalion, we dug in and waited for the word to renew the attack on Schmidt, but because of the problems that the Kall Trail presented, the attack was delayed. No tanks or supplies were getting through. The Germans could not shell our position with their regular artillery because of the reverse slope, but they were able to use mortar, due to the higher trajectory. We hadn't eaten in three days, except for a roll of life savers, which I shared with a friend, and there wasn't any part of me that wasn't cold, wet or damp. The damp part was having the hell scared out of me. While in this position outside of Kommerscheidt, the wounded increased at an alarming rate, and they could not get proper treatment. Our medics negotiated a temporary truce. I was told by our medics that the Germans checked each stretcher to make sure that only the most seriously wounded were being evacuated.

Sometime on the 8th of November 1944, word was radioed that we were trapped and that our troops would not be able to break through to us. We were to abandon our position, and all our mortars and machine guns were to be destroyed. We were to break up into small groups and get back to our original company areas. Since I was in charge of the 60 mm mortars, I destroyed the mortar sights with the butt of my rifle, and buried the base plates, bipods, and the mortar tubes in different spots and camouflaged the area.

When the group I was with took off late that night, we went down the Kall Trail and across the stone bridge over the Kall River. It was guarded by troops. We came upon it very quickly, and it was very dark and raining. My Platoon Sgt. and I, in discussing this years later, are sure that the troops were Germans, but since our group was larger than theirs, and this happened so fast, no action resulted. After crossing the bridge, we went cross country out of the Kall Valley, up some very steep slopes, suitable only for mountain goats. Everyone was very quiet, and we received no incoming fire. The Germans apparently had no idea that we had left our position. It was during this time that someone lost their helmet. It went crashing down the rocky slope to the bottom of the valley, making a tremendous amount of noise. After getting away without being detected, we thought we had had it, but nothing happened.

When we arrived at the top of this valley, we came to a flat area where we were challenged in English by a sentry. Whoever was leading us, satisfied the outpost that we were GI's, and we passed through to our company area. We were too tired to dig in. We just laid down and went to sleep. At first light, when I awoke, I was covered with the first snow of the season. The medics arrived and were checking everyone. When they came to me, they asked me how I was, and I said that other than being cold, wet and hungry, I was O.K. They asked me how my feet were. I said, "O.K.", and proceeded to take my M1 and hit my left foot with the butt of my rifle and felt nothing. They had me take my boots off and examined my feet. They were as white as the new snow. The medics wrote out a casualty tag, and put it on me. They brought up a stretcher and told me to get on it, which I thought was great. It was great until the circulation started to try to get back in my legs and feet.

When they took my M1, I saw for the first time that six inches of the barrel were missing, probably removed by shrapnel. I have no idea when this happened, because my rifle was always within my reach. This started me on my way to the States, through numerous hospitals in France and England, and on a hospital ship, the S.S. Exchequer.

S.S. Exchequer

I never did find out who led us out of the trap. Whoever did, was one hell of a soldier. The night was so dark that you couldn't see 4 feet in any direction. In my group there were 18 of us. We were lucky. Some groups didn't make it. We did.

At the Regimental reunion in Washington, Pa., I asked my Platoon Sgt. who the hell lost their helmet that night. His face turned red, and he confessed that it was his, and we had a good laugh.

I served in the 110th Regiment of the 28th Division from 1942 to 1944, joining them at Camp Livingston, La. I ended up with Trench Feet in the Hurtgen Forest fiasco and spent nine months in eight Army hospitals.

The Hurtgen Forest - I remember it as being dark, dreary, for-boding, sinister, close, and desolate. I was very cold, wet, hungry, dirty, and very apprehensive. At this stage I would like to make a personal observation. The Hurtgen Forest Schmidt operation took a prime division, the 28th, and piece meal fed it into the German meat grinder. From all the articles I have read and having personally been there, I believe that a gross error by our commanding officers was made, and they were never made to account for this disaster. General Cota, the commanding General of the 28th Division, lost 6,184 men # in a 7 day period, and I was one of them. It put a lot of crosses in Europe and a lot of injured men in hospitals. This division was not used properly, or during the Battle of the Bulge, it really could have given the Germans fits.

Mortars

1. In the battle for the Hurtgen Forest, I was a Sgt. in charge of the 1st mortar squad. I was also acting section leader in charge of the other two mortar squads. In planning the attack, the 4th platoon Sgt. went over the map of the attack area and gave it to me. I was to follow the company attack with the 3 mortar squads when the objective was secure. At one of the reunions, the 4th platoon Sgt. and I discussed this and neither of us could figure out where the mortar section leader was at this time. According to the organization table, a Staff Sgt. is in charge of the mortar section (3 squads). At the time we entered the Hurtgen Forest the Staff Sgt' s name is on the roster, so the mystery persists

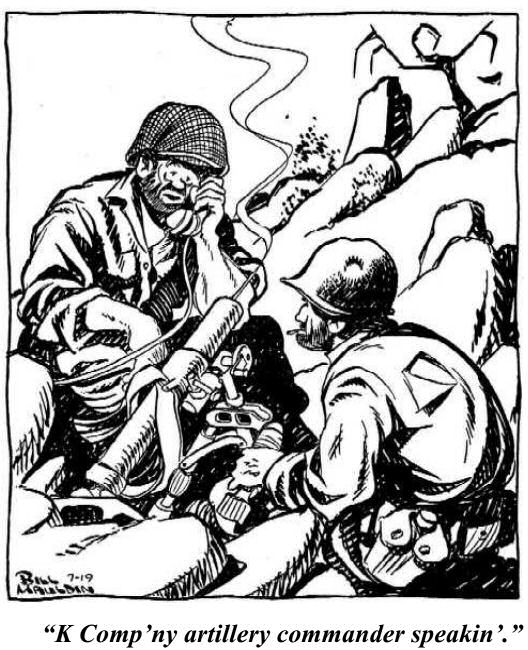

2. Mortars are the artillery of an infantry company. Outside of the bazooka, they carry more viciousness and wallop per pound than any weapon the infantry has. The guys who operate them are at a big disadvantage. Because of the mortar's limited range, they have to work so close to the front that they are a favorite target for snipers, patrols, shells, and counter fire. "Knocked-out mortar positions earn Iron Crosses for ambitious young Herrenvolk."

Bill Mauldin, "Up Front", 1944

3. General Major Rudolf Freiherr von Gersdorff said, "Most German casualties came from American mortar fire, particularly effective in the woods".

| 4 . | Mortar | Weight - 42 lbs. |

| shells | Weight - 3 lbs.- TNT | |

| Amo-bags | Holds 3 shells front - 3 shells back | |

| Range | 2000 yards | |

| Squad | 5 men | |

| Squad leader has rank of Sgt. He is assigned: | ||

| Field glasses | ||

| Sight | ||

| Lensatic compass | ||

| Mortar base plate | ||

| M1 rifle | ||

| Gunner carries: | ||

| Mortar tube | ||

| Bipod | ||

| 45 pistol | ||

| Asst. Gunner carries: | ||

| Amo bag - 6 shells = 18 lbs. TNT | ||

| 45 pistol | ||

| 1st ammo carrier carries: | ||

| Amo bag - 6 shells = 18 lbs. TNT | ||

| Carbine | ||

| 2nd ammo carrier carries: | ||

| Amo bag - 6 shells = 18 lbs. TNT | ||

| Carbine | ||

We never carried the full compliment of ammunition that the training manual states. (12 rounds per man = 36 lbs.). This was because of the weight, which would have slowed us up. In combat you have to be able to move fast to survive.

In remembrance of Albert W. Burghardt

Albert Burghardt passed away on May 6, 2016, at the age of 94.

I wish to thank Dave Burghardt for sharing his dad's memoirs. Scorpio.